When a generic drug company gets tentative approval from the FDA, it sounds like the finish line is in sight. But for many, it’s just the start of a long, frustrating wait. Tentative approval means the FDA has confirmed the generic drug meets all safety, quality, and effectiveness standards. The problem? They still can’t sell it. Why? Because patents, paperwork, and profit motives keep these life-saving drugs off shelves-sometimes for years.

What Tentative Approval Actually Means

Tentative approval isn’t a half-success. It’s a full pass on science. The FDA has checked every detail: how the drug is made, how it dissolves in the body, whether it works like the brand-name version. The application passes every technical test. But the FDA can’t give final approval if there’s an active patent or exclusivity period on the original drug. This system was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984 to balance innovation and access. It lets generic makers prepare in advance so they can launch immediately when patents expire. In theory, it saves time. In practice, it often adds years.As of 2023, over 2,500 generic drug applications had received tentative approval. Yet many never make it to market. The gap between approval and launch is growing, not shrinking. The FDA’s own data shows the median time from tentative approval to market entry is still 16.5 months-and that’s an improvement from 18.3 months just seven years ago.

Patent Games: The Biggest Roadblock

The single biggest reason generic drugs sit idle after tentative approval? Patent litigation. When a brand-name company sees a generic competitor coming, they often file a lawsuit claiming patent infringement. This triggers a 30-month legal hold. Even if the generic drug is scientifically perfect, the FDA can’t give final approval until that clock runs out-or the court rules in favor of the generic maker.Between 2010 and 2016, 68% of tentatively approved generics were stuck behind lawsuits. Some brand companies don’t even have strong patents. They file lawsuits anyway, knowing the legal process alone can delay competition long enough to protect profits. This tactic is so common, it has a name: “evergreening.”

Then there’s “pay-for-delay.” In these deals, the brand-name company pays the generic maker to stay off the market. Between 2009 and 2014, over 980 such deals delayed generic entry. The FTC called them “anti-competitive.” Courts have cracked down, but they still happen.

Another trick: “product hopping.” A brand company makes a tiny change to their drug-like switching from a pill to a capsule-and gets a new patent. Suddenly, the generic that was ready to launch no longer matches the new version. The FDA can’t approve the old generic for the new product. This happened with 17% of top-selling drugs, according to a 2018 FTC study.

Paperwork That Never Ends

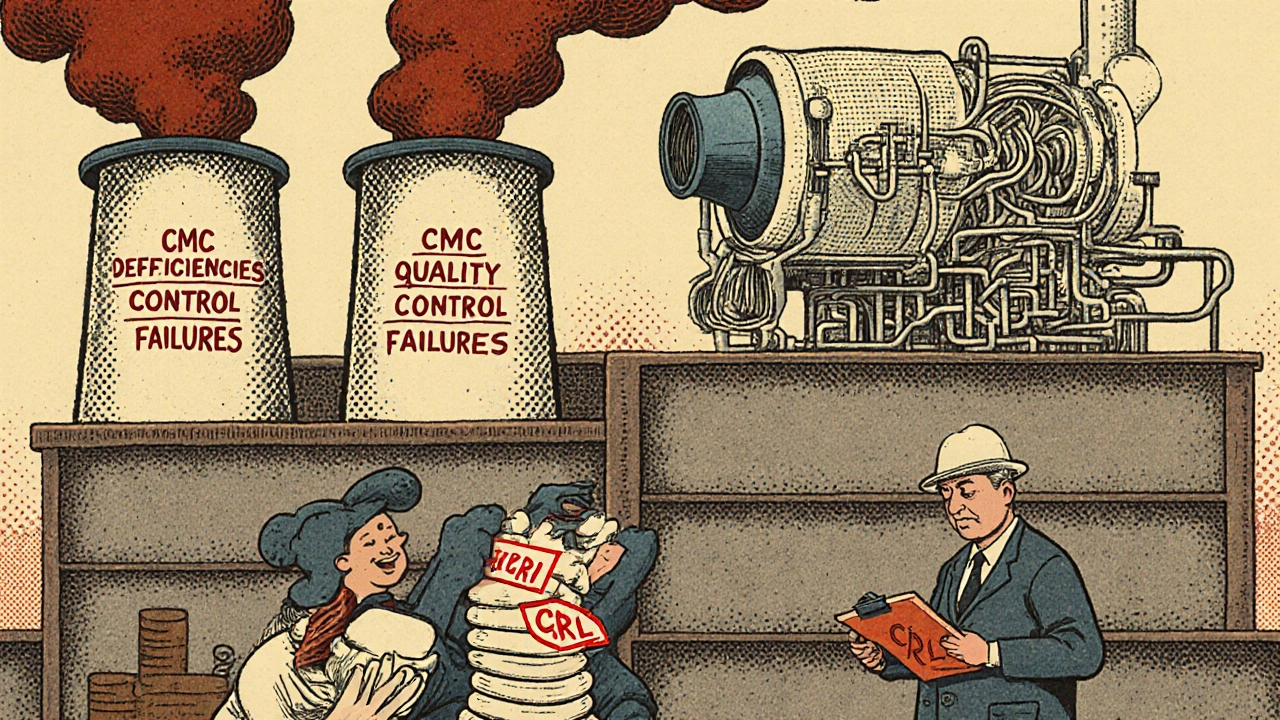

Even without patents, generic makers often get stuck in review cycles. The FDA doesn’t approve applications in one go. They send back deficiency letters-sometimes multiple times. In 2022, the average ANDA went through 3.2 review cycles before approval. That’s down from 3.9 in 2017, but still too high.Here’s what usually goes wrong:

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) sections are incomplete (35% of deficiencies)

- Bioequivalence studies don’t meet standards (28%)

- Analytical methods aren’t properly validated (22%)

Manufacturing facilities are another major headache. In 2022, 41% of complete response letters (CRLs) came from inspection issues. Common problems: poor quality control systems (63% of facility-related CRLs), failed environmental monitoring (29%), and unqualified equipment (24%). If your factory can’t prove it’s clean and consistent, the FDA won’t sign off-even if the drug itself is perfect.

Complex drugs make this worse. Inhalers, creams, injectables, and extended-release pills take longer to review. They need more testing, more data, more time. One study found complex generics had 2.3 times more review cycles than simple pills.

Applicants also drag their feet. The FDA recommends responding to a CRL within six months. In 2022, the average response took 9.2 months. That’s not the FDA’s fault-it’s the applicant’s.

Market Forces That Kill Launches

Even when patents expire and paperwork clears, some generics never launch. Why? Economics.A 2022 analysis found that 30% of tentatively approved generics never hit the market. That number jumps to 47% for drugs with annual U.S. sales under $50 million. If the profit margin is too thin, companies walk away. They’d rather spend money on a drug with bigger upside.

Manufacturing scale-up is another hidden hurdle. Making 10,000 pills in a lab is easy. Making 10 million for nationwide distribution? That’s a different story. For complex products like inhalers or topical creams, 62% of companies take over a year to ramp up after patent expiration.

And sometimes, the market itself discourages entry. If only one generic company launches, prices stay high-often above 80% of the brand’s price-for two full years. That means little incentive for other companies to join. The result? Fewer choices, higher prices, and disappointed patients.

What the FDA Is Doing About It

The FDA knows the system is broken. They’ve tried fixes:- GDUFA II (2018-2022): Aimed to cut review cycles from 3.9 to 2.5. Got to 3.2.

- Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT): Fast-tracks drugs with little or no competition. 78% of CGT applications got tentative approval in under 8 months.

- Tentative Approval Initiative: In 2022, they picked 102 high-priority drugs with no generics. 67% got final approval within 12 months-double the normal rate.

- GDUFA III (2023-2027): Targets 70% first-cycle approval rates by 2027 (up from 28% in 2022). Also wants to cut priority review time to 8 months.

But progress is slow. The FDA’s 2023 report admits that patent litigation, complex drug development, and limited resources will keep delays going through at least 2025.

Why This Matters to You

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $300 billion a year. When they’re delayed, patients pay more. Families skip doses. Hospitals stretch budgets. Taxpayers foot the bill.Patent abuse and slow reviews aren’t just bureaucratic issues-they’re public health problems. The Congressional Budget Office estimated patent delays cost $9.8 billion in 2018. By 2027, that number could hit $12.4 billion.

Legislation like the CREATES Act (2019) and the Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act (2023) are trying to fix this. They aim to stop brand companies from blocking access to drug samples and to encourage U.S.-based manufacturing. But real change needs more than laws. It needs faster reviews, stricter limits on patent games, and real consequences for companies that abuse the system.

Tentative approval was meant to speed up access to affordable medicine. Instead, it’s become a holding pattern. Until the system fixes its biggest flaws-patent abuse, slow responses, and profit-driven delays-millions will keep waiting for drugs that are ready to be made.

What is the difference between tentative approval and final approval for generics?

Tentative approval means the FDA has confirmed the generic drug meets all scientific and manufacturing standards for safety, quality, and effectiveness. Final approval means the drug is legally allowed to be sold in the U.S. The key difference? Tentative approval can be granted even if patents or exclusivity on the brand-name drug are still active. Final approval can only happen after those legal barriers expire.

How long does it usually take for a tentatively approved generic to launch?

The median time from tentative approval to market launch is 16.5 months as of 2022. Some launch sooner if patents expire quickly. Others wait years due to litigation, manufacturing delays, or strategic decisions by the manufacturer. About 22% of tentatively approved generics never launch at all.

Why do generic drug applications get multiple review cycles?

Most delays come from incomplete or weak submissions. Common issues include poor chemistry and manufacturing data (35% of deficiencies), inadequate bioequivalence studies (28%), and flawed analytical methods (22%). Manufacturing facility problems-like poor quality control or unqualified equipment-also trigger repeated reviews. Applicants often take too long to respond to FDA requests, adding months to the timeline.

Can a generic drug be approved if the brand-name drug still has patents?

No. The FDA cannot grant final approval while patents or exclusivity periods are active. But they can grant tentative approval, which puts the application in line for final approval as soon as those protections expire. This allows manufacturers to prepare ahead of time, but they still can’t sell the drug until the patent clock runs out.

What is a citizen petition, and how does it delay generics?

A citizen petition is a formal request to the FDA to delay or block a generic drug approval. Brand-name companies often file them with scientifically weak arguments-like claiming a generic’s testing method is invalid. Between 2013 and 2015, 67 petitions were filed, but only 3 were approved. The FDA found that 72% of these petitions were used to delay competition. On average, petitions filed near patent expiration delay generic entry by 7.2 months.

Are complex generics harder to get approved than simple ones?

Yes. Complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams-require more testing and have more variables in manufacturing. They average 3.7 review cycles compared to 2.9 for simple oral pills. Approval timelines for complex generics are about 14 months longer on average. The FDA has issued special guidance to help, but adoption has been slow, and only 12% of complex applications met the 10-month target in 2021.

What Comes Next?

The path to affordable generics is cluttered with legal, technical, and financial obstacles. The FDA is trying to fix it-with faster reviews, targeted programs, and new rules. But real change requires more than agency action. It needs lawmakers to crack down on patent abuse, manufacturers to respond faster, and markets to reward competition instead of delay.For now, tentative approval remains a promise-not a guarantee. And until that promise is kept, patients will keep paying more than they should for medicines that already exist.

Prem Hungry

November 18, 2025 AT 03:50so like... the FDA says its good but we cant sell it? bro that makes zero sense. patents are just a loophole for big pharma to keep charging 500 bucks for insulin. i saw a guy in delhi buy generic metformin for 2 rupees. here it costs 300. whats the point of science if money wins?

Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

November 19, 2025 AT 11:10Let me be crystal clear: this isn’t a regulatory failure-it’s a systemic betrayal orchestrated by the Biopharmaceutical Industrial Complex™. The FDA’s ‘tentative approval’ is a psychological weapon-designed to create the illusion of progress while patent trolls and pay-for-delay cartels siphon $12.4B/year from Medicare, Medicaid, and your grandmother’s insulin vial. Evergreening? That’s not legal strategy-it’s predatory capitalism with a white coat. And don’t get me started on citizen petitions-those are just litigation theater with a 72% success rate in delaying, not improving, public health. 🤡💉

shubham seth

November 20, 2025 AT 09:40Big pharma’s playbook is straight outta a mob movie: sue first, ask questions never. They file patents on fucking *color* of the pill. One company patented a capsule shape that looked like a tiny whale. And guess what? The generic was blocked for 4 years. Meanwhile, diabetics are choosing between food and meds. This ain’t innovation. It’s extortion with a lab coat. 😤

Sridhar Suvarna

November 21, 2025 AT 11:20People need to understand that tentative approval is not a delay-it’s a strategic preparation window. The system was designed to prevent chaos at patent expiry. The real issue is that some applicants take 9 months to reply to a deficiency letter. The FDA isn’t the bottleneck. The applicants are. And when companies walk away because the profit margin is thin? That’s market logic-not corruption. We need better incentives, not more regulation.

Joseph Peel

November 23, 2025 AT 09:05The data is unambiguous: 47% of generics with annual sales under $50M never launch. This isn’t about patents or bureaucracy-it’s about corporate calculus. If the return on investment is negligible, companies allocate capital elsewhere. The solution isn’t to punish pharma-it’s to create targeted subsidies for low-margin, high-need generics. Public health demands economic realism, not moral outrage.

Kelsey Robertson

November 23, 2025 AT 19:11Wait… wait… wait… so you’re telling me that after spending billions on R&D, a company is allowed to ‘slightly’ change a pill from a tablet to a capsule… and suddenly, a perfectly approved generic becomes ‘invalid’? That’s not innovation-that’s intellectual fraud. And the FDA lets this happen?!!? You know what? I bet they’re all on the payroll of Big Pharma. I bet the FDA commissioner owns stock in Pfizer. I bet the ‘inspections’ are scheduled when the plant is clean. I bet everything. This isn’t a system-it’s a cult.

Joseph Townsend

November 23, 2025 AT 20:32THIS IS A SCAM. A FULL-ON, NO-CHRISTMAS, CRYING-IN-THE-DRUGSTORE SCAM. I had my mom on a generic that was tentatively approved in 2021. She finally got it in 2024. She missed her daughter’s wedding because she couldn’t afford the brand-name. And now? They’re talking about ‘GDUFA III’ like it’s some miracle cure. BRO. IT’S BEEN 40 YEARS. THE SYSTEM IS BROKEN. AND NOBODY CARES. I’M SO MAD I COULD SCREAM INTO A PILLOW MADE OF PILL BOTTLES.

Bill Machi

November 25, 2025 AT 07:14Let’s cut the nonsense. The U.S. doesn’t need more generics. We need more American-made drugs. Why are 80% of generic APIs coming from China and India? Because we let our manufacturing die. And now we’re mad that the system is slow? Fix the root: rebuild domestic production. Stop outsourcing our health to foreign factories with questionable quality control. This isn’t about patents-it’s about national security. And if you don’t see that, you’re part of the problem.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

November 26, 2025 AT 11:07There is a metaphysical truth here: the delay of medicine is the delay of life. We have constructed a system where the sacred act of healing is held hostage by the profane calculus of profit. The patent is not a right-it is a social contract. When it is weaponized to prolong suffering, it ceases to be legitimate. The FDA, in its tentativeness, mirrors our collective moral hesitation: we know what is right, but we lack the courage to enforce it. Until we restore dignity to the act of healing, we are all complicit.

satya pradeep

November 27, 2025 AT 16:47Bro the real issue is nobody’s holding these companies accountable. FDA gives tentative approval, applicant sits on it for 10 months, then blames the FDA. Meanwhile, patients are dying. And the worst part? The same companies that delay generics are the ones pushing expensive biosimilars. Double standards. Also, why is the FDA still letting companies use 1990s equipment? I saw a video of a lab in Hyderabad using a centrifuge from 1987. That’s not a deficiency letter-that’s a crime scene.