Administering medications through a feeding tube sounds simple-until it goes wrong. A crushed pill that clogs the tube. A delayed dose because the meds weren’t flushed properly. A patient’s seizure because their phenytoin levels dropped. These aren’t rare mistakes. They happen daily in hospitals and home care settings, often because no one stopped to ask: Is this drug even meant for the tube?

Not All Pills Belong in a Tube

Just because a pill fits through the opening doesn’t mean it should go in. Extended-release tablets, enteric-coated capsules, and sustained-release formulations are designed to dissolve slowly in the gut. Crush them, and you destroy that design. Valganciclovir (Valcyte®), mycophenolate (Cellcept®), and finasteride (Proscar®) are absolute no-gos for crushing. Breaking them open can release toxic doses all at once or render them useless. Even something as common as duloxetine capsules contains tiny enteric-coated pellets-those aren’t meant to be crushed, and they’ll clog a small-bore tube instantly.The NIH studied 323 oral medications for tube compatibility. Only 78% of immediate-release tablets dissolved well in water within five minutes. For extended-release versions? Just 32%. That’s not a small gap-it’s a safety chasm. Some medications, like Prevacid® SoluTabs, are exceptions. They’re specially formulated to disperse evenly in water without leaving grit behind. Most others? Not even close.

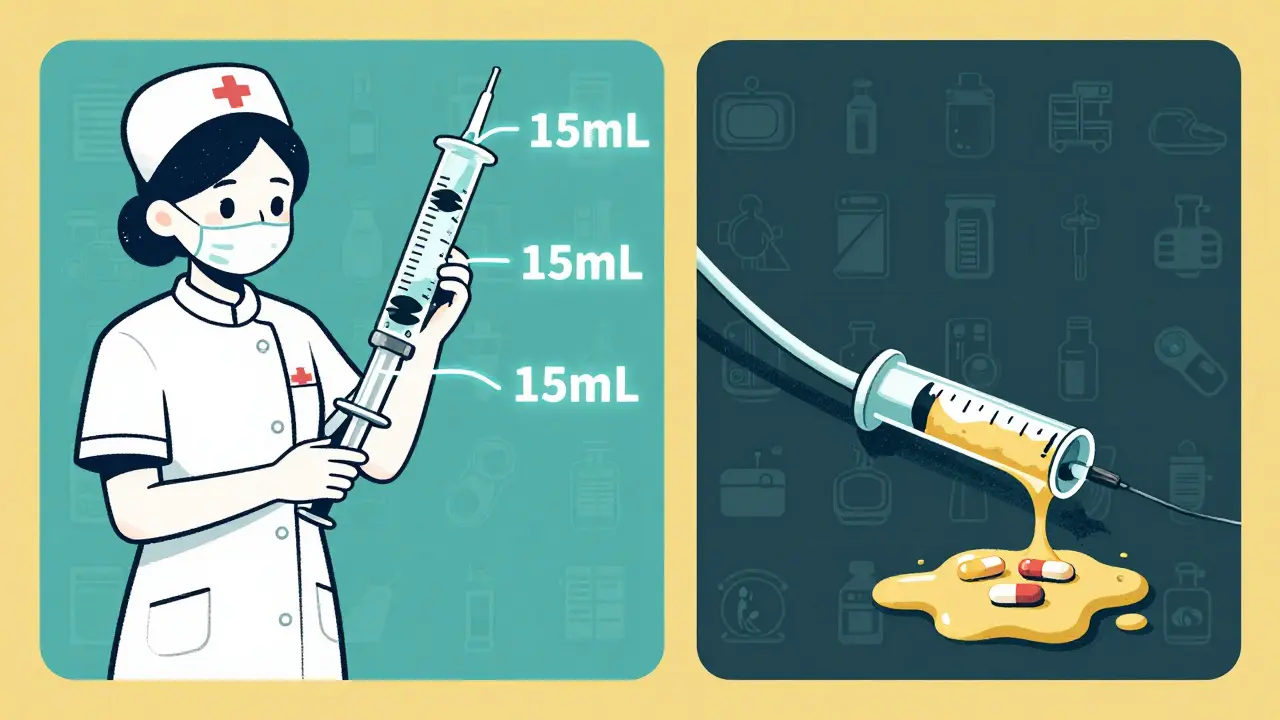

Flushing Isn’t Optional-It’s Life-Saving

You wouldn’t pour syrup into a garden hose and expect it to flow. Yet that’s exactly what happens when meds aren’t flushed properly. The standard? At least 15 mL of water before the first med, 15 mL between each med, and another 15-30 mL after the last one. Cleveland Clinic says you need 15 mL of flush for every 10 mL of medication. That’s not a suggestion-it’s the minimum to keep the tube clear.Most nurses report using less than 10 mL. Why? Time pressure. Lack of training. Assumption that “it’ll be fine.” But 65% of tube blockages are caused by medication residue. A single improperly flushed dose can lead to a blocked tube, a delayed antibiotic, or a missed insulin dose. And if you’re giving multiple meds? Flush after each one. Don’t group them. Don’t assume the feed flushes them out. Feeding formula doesn’t clean tubes-it coats them.

Tube Size Matters More Than You Think

Not all feeding tubes are the same. Nasogastric (NG) tubes can be as narrow as 5 French (1.7 mm). G-tubes might be 16 French (5.3 mm). Smaller tubes? They’re like straws. Even a finely ground tablet can form a paste that sticks. If you’re using an 8 French or smaller tube, avoid anything with fillers, coatings, or insoluble particles. Liquid formulations are safer-but even then, check the label. Many liquid meds contain suspensions with particles that settle and clog.Manufacturers are supposed to test their drugs on at least three different tube types before claiming they’re safe. But here’s the problem: no over-the-counter drug is officially labeled for enteral use. That means nearly every medication given through a tube is being used off-label. You’re relying on pharmacist expertise, institutional guidelines, or a published study-not a box label.

When to Stop and Ask a Pharmacist

If you’re unsure, stop. Don’t guess. Don’t Google. Don’t rely on memory. Call the pharmacy. Every hospital should have a feeding tube med checklist, but in home care? That’s where the gaps widen. Pharmacists aren’t just dispensers-they’re the last line of defense. They know which tablets can be crushed safely, which liquids are compatible with feeding formulas, and which drugs need serum level checks after switching from capsule to liquid.For example: switching from extended-release diltiazem to immediate-release means you might need to give it three times a day instead of once. And you must monitor blood levels. Same with phenytoin-its therapeutic range is razor-thin (10-20 mcg/mL). Change the form, and you risk toxicity or underdosing. That’s not a minor tweak. It’s a clinical decision.

Tube Placement Check: The First Step You Can’t Skip

Before you even open a pill bottle, confirm the tube is where it should be. A misplaced NG tube in the lungs? Giving meds there can be fatal. pH testing of aspirate is the quickest method-gastric fluid is acidic (pH ≤5). If you’re unsure, get an X-ray. Document it. Every time. No exceptions.Studies show that 15-20% of all enteral feeding-related adverse events come from errors in tube placement verification. Nurses are busy. Medications are urgent. But skipping this step isn’t cutting corners-it’s gambling with lives.

What You Should Never Do

- Don’t mix meds with feeding formula. Even if it seems convenient, it can cause precipitation, reduce absorption, or block the tube. Always flush between meds and feed.

- Don’t use carbonated water. Bubbles can create air pockets that interfere with flow and measurement.

- Don’t use juice or soda. Acidic drinks can interact with meds or degrade tube material.

- Don’t crush enteric-coated, extended-release, or sustained-release tablets. Ever.

- Don’t assume a liquid form is safe. Some liquids contain alcohol, sugar, or preservatives that aren’t compatible with long-term feeding.

Real-World Consequences

At one VA hospital, they had 12 tube blockages per month. After implementing a pharmacist-led verification system and mandatory flushing logs, that dropped to 7 in three months. Then, with electronic alerts in their system blocking unsafe orders, it fell to just 2. That’s a 40% reduction in complications-just by fixing the process.On the flip side, there’s the case of a home care patient given crushed extended-release diltiazem. The drug released too fast. Blood pressure crashed. They ended up back in the ER. The family didn’t know the pill was modified-release. The nurse hadn’t checked. The pharmacy wasn’t consulted. It was preventable.

Training and Documentation: The Hidden Safety Net

Nurses need at least 8-12 supervised administrations before they’re considered competent. That’s not just about technique-it’s about building the habit of double-checking. Training should include:- How to read a drug’s formulation type

- How to prepare each med correctly

- When to flush and how much

- How to recognize early signs of blockage

Documentation isn’t busywork. It’s legal and clinical protection. Every time you give a med through a tube, you must record:

- Medication name and dose

- Preparation method (crushed? dissolved? liquid?)

- Flush volume used before, between, and after

- Tube placement verification method and result

- Any resistance or blockage noted

Failure to document? That’s an administration error. And it’s just as dangerous as giving the wrong dose.

The Bigger Picture

Enteral feeding supports over 1.5 million people in the U.S. alone. Medication errors through tubes are one of the top 10 preventable safety issues in healthcare, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. The FDA’s 2021 draft guidance is the first step toward standardizing testing for tube compatibility-but it’s still not law. Until then, the burden falls on clinicians.The good news? Change is happening. Pharmacist-led protocols, electronic alerts, and better training are reducing errors. The bad news? Many still operate on outdated habits. “We’ve always done it this way” isn’t a valid safety protocol.

Every time you give a med through a tube, you’re not just delivering a drug. You’re managing risk. And that means knowing the difference between what’s convenient and what’s safe.

Can I crush any pill and give it through a feeding tube?

No. Extended-release, enteric-coated, and sustained-release medications should never be crushed. Crushing them can cause toxic spikes, reduce effectiveness, or clog the tube. Examples include Valcyte®, Cellcept®, and Proscar®. Always check with a pharmacist before crushing any pill.

How much water should I use to flush a feeding tube?

Use at least 15 mL of water before the first medication, 15 mL between each medication, and 15-30 mL after the last one. For every 10 mL of medication, use 15 mL of flush. More is better-especially with smaller tubes. Never rely on the feeding formula to flush the tube.

Is it safe to mix medications with the feeding formula?

No. Mixing meds with feeding formula can cause chemical reactions, reduce absorption, or form clumps that block the tube. Always flush the tube thoroughly before and after giving meds, and never add medications directly to the formula unless there’s published, verified compatibility data.

Do I need to check tube placement every time?

Yes. Always verify placement before giving any medication or feeding. Use gastric pH testing (pH ≤5 indicates correct placement) or confirm with X-ray if unsure. A misplaced tube can lead to aspiration, pneumonia, or death. Never assume it’s still in the stomach.

What should I do if the tube gets blocked?

First, try flushing with warm water using a 60 mL syringe and gentle push-pull motion. Don’t force it. If that doesn’t work, try a commercial declogging solution or pancreatic enzymes (like pancrelipase) mixed with water. If still blocked, call for help-don’t delay. A blocked tube can mean missed meds, dehydration, or infection.

Are liquid medications always safer than tablets?

Not always. Some liquid meds contain insoluble particles, alcohol, or preservatives that can irritate the gut or damage the tube. Always check compatibility. A liquid isn’t automatically safe just because it’s not a pill. Pharmacist verification is key.

Why isn’t there a label saying a drug is safe for feeding tubes?

As of now, no over-the-counter or prescription drug in the U.S. is officially labeled for enteral tube administration. Manufacturers aren’t required to test for it. So even if a drug is commonly given through tubes, it’s still off-label use. That’s why pharmacist expertise and institutional guidelines are critical.

Next Steps for Safe Practice

- Ask your pharmacy for a list of tube-safe medications at your facility.

- Ensure every nurse has access to a feeding tube med reference guide.

- Implement electronic alerts to flag unsafe orders (like crushed extended-release drugs).

- Train staff annually-not just on how to flush, but on why it matters.

- Document every step. If it’s not written down, it didn’t happen.

Enteral feeding saves lives. But giving meds through a tube? That’s a precision task. It demands knowledge, discipline, and respect for the science behind each pill and each drop of water. Get it right-and you’re not just preventing a clog. You’re preventing a crisis.

Sachin Bhorde

December 16, 2025 AT 09:22Man, I’ve seen so many nurses just wing it with tube meds-crush everything like it’s candy. But dude, that Valcyte thing? Total nightmare waiting to happen. We had a guy in ICU almost die when someone crushed his extended-release diltiazem. Pharma needs to label this shit properly. Until then, we’re all playing Russian roulette with a 60mL syringe.

Joe Bartlett

December 17, 2025 AT 06:35Flush with water. Simple. Done. No drama. UK nurses do this right. No excuses.

Chris Van Horn

December 18, 2025 AT 13:11Let me be perfectly clear: the fact that this post even needs to exist is a grotesque indictment of American clinical incompetence. The FDA’s inaction is not merely negligent-it’s criminally lax. We’re allowing untested, off-label, unregulated pharmaceutical administration to become standard practice because someone thought ‘it’s just a tube.’ This isn’t healthcare. It’s a horror show with IV poles.

Virginia Seitz

December 20, 2025 AT 10:14YES. 🙌 I work in home care and this is EVERYDAY. I’ve started carrying a little card in my pocket with the no-crush list. Saved a guy’s kidneys last week. 💪

Peter Ronai

December 21, 2025 AT 14:13Oh please. You think flushing with 15mL is enough? That’s kindergarten-level thinking. Real professionals use 30mL. Always. And if you’re not using sterile water? You’re a liability. Also, who told you to use warm water? That’s a myth. Cold water is better for dissolving meds. I’ve published papers on this.

Steven Lavoie

December 23, 2025 AT 05:58As someone who’s worked in both ICU and home care, I’ve seen the gap between protocol and practice. It’s not about laziness-it’s about systems failing people. Nurses aren’t trained to be pharmacists. We need better tools, not more guilt. This post is a good start, but let’s build the infrastructure to support it.

Michael Whitaker

December 25, 2025 AT 05:02Actually, I’ve been told by a very reputable consultant (PhD, Harvard, published in NEJM) that the 15mL flush is outdated. The current standard, based on 2023 multicenter trials, is 20mL for tubes under 10F and 25mL for larger. Also, carbonated water? Not entirely taboo-if you use it sparingly and only with non-alkaline meds. I’ve seen it dissolve stubborn clogs without damage.

Kent Peterson

December 27, 2025 AT 02:50Let’s be real: this is all just fear-mongering. I’ve been giving crushed pills through NG tubes for 18 years. No one’s died. The ‘studies’? Paid for by Big Pharma to sell you expensive liquid versions. Crush the pill. Flush with tap water. Move on. Stop overcomplicating things. The system is broken because we listen to people like you.

Josh Potter

December 27, 2025 AT 15:45Bro. I just got back from a 12-hour shift. We had THREE blocked tubes. I was so tired I almost skipped the flush between meds. Then I remembered this post. I flushed 30mL after each one. No clogs. No drama. Just… clean tubes. Thanks for the reminder. We need more of this stuff.

Evelyn Vélez Mejía

December 29, 2025 AT 15:04Enteral feeding is not a medical procedure-it’s a metaphysical negotiation between chemistry, biology, and human fallibility. Each pill crushed is a small surrender to convenience; each flush is an act of reverence for the body’s fragile equilibrium. We are not technicians-we are stewards of thresholds. And thresholds, once crossed, do not always return.

Meghan O'Shaughnessy

December 30, 2025 AT 04:39My mom’s on a G-tube. I read this whole thing. I printed it. Gave it to her home nurse. She cried. Said she’d never seen it all laid out like this. Thanks for writing this.

Kaylee Esdale

December 31, 2025 AT 14:55Just a reminder: if you’re using juice to flush? Stop. It’s not helping. And if you’re crushing pills because you’re ‘in a hurry’? You’re not helping anyone. Slow down. Breathe. Your patient’s life isn’t on a timer.

Pawan Chaudhary

January 1, 2026 AT 08:58India is catching up! We started pharmacist-led tube med audits in our hospital last year. Blockages down 60%. Nurses now ask before crushing. Small wins, but they matter. Keep sharing this!

Jonathan Morris

January 2, 2026 AT 10:35Notice how no one mentions the real issue: the FDA and pharmaceutical companies are deliberately avoiding tube compatibility testing to avoid liability. This is a profit-driven cover-up. They know crushing extended-release meds causes harm-but they’d rather you blame the nurse than admit their pills are unsafe for the very people who need them most.