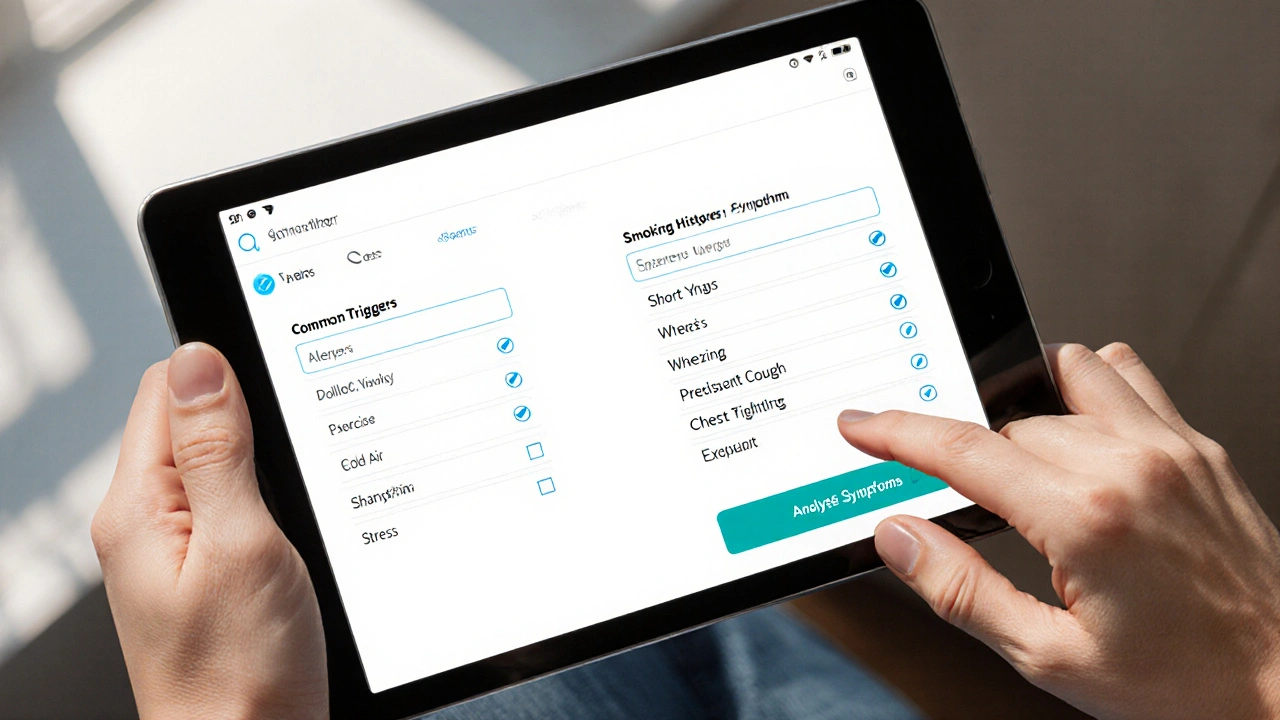

COPD vs Asthma vs Overlap Symptom Checker

Enter your information and click "Analyze Symptoms" to get insights about potential respiratory conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Both COPD and asthma affect the airways but differ in triggers, reversibility, and long‑term damage.

- About 15‑20% of adults experience features of both conditions, known as asthma‑COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS).

- Smoking and genetic predisposition are common risk factors, while allergic reactions are more asthma‑specific.

- Accurate diagnosis relies on spirometry, symptom history, and response to bronchodilators.

- Management combines inhaled steroids for inflammation with bronchodilators for airflow, plus lifestyle changes.

When you hear COPD and asthma mentioned together, it can feel like a medical tongue‑twister. Yet the reality is simple: they are two respiratory diseases that sometimes share symptoms, especially in people over 40 who have smoked or been exposed to pollutants. This article breaks down what each condition is, where they overlap, and how to keep your lungs working as well as possible.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease is a progressive lung disease that makes it hard to exhale fully, leading to trapped air and shortness of breath. It’s most often linked to long‑term smoking, but occupational dust and air pollution also play big roles. COPD is characterized by chronic inflammation, airway narrowing, and destruction of the tiny air sacs (alveoli) that exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Asthma is a condition where the airways become overly sensitive, swelling and tightening in response to triggers like pollen, cold air, or exercise. Unlike COPD, asthma’s airway narrowing is usually reversible with medication, and the disease can start in childhood. Asthma involves inflammation of the bronchial walls and a hyper‑responsive airway smooth muscle.

When a patient shows signs of both diseases, clinicians refer to the situation as asthma‑COPD overlap syndrome (sometimes called ACOS). It’s not a separate disease but a label that signals a mixed pattern of airflow limitation.

What Makes COPD Different?

Think of COPD as a slow‑burning fire. The damage accumulates over years, and even after quitting smoking, the lungs don’t fully recover. Key traits include:

- Age of onset: Usually after 40.

- Primary cause: Long‑term exposure to irritants, especially tobacco smoke.

- Reversibility: Limited - bronchodilators help but never restore normal lung function.

- Inflammation type: Neutrophil‑driven, leading to mucus hyper‑secretion and tissue breakdown.

Because the structural damage is permanent, COPD management focuses on slowing progression and treating flare‑ups.

What Sets Asthma Apart?

Asthma is more like a firecracker-quick, intense, but often easily stopped. Its hallmarks are:

- Age of onset: Can start in childhood or early adulthood.

- Primary triggers: Allergens (pollen, dust mites), viral infections, exercise, cold air.

- Reversibility: High - inhaled bronchodilators and steroids usually bring airflow back to normal.

- Inflammation type: Eosinophil‑dominant, driven by allergic pathways.

Asthma can be well‑controlled with a proper inhaler regimen, allowing most people to lead normal lives.

How the Two Conditions Overlap

Overlap isn’t rare. Studies from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) estimate that up to one‑fifth of adults with COPD also meet asthma criteria. The overlap syndrome shares features from both sides:

- Persistent airflow limitation like COPD.

- Variable bronchodilator response similar to asthma.

- Mixed inflammatory profile - both neutrophils and eosinophils.

Patients with overlap often experience more frequent exacerbations, a faster decline in lung function, and a higher need for hospital care. Recognizing the overlap early can change treatment direction.

Shared Risk Factors

Both diseases have a few common ground:

- Smoking is the single biggest preventable cause of COPD and also worsens asthma control. Even a few cigarettes a day can increase airway hyper‑responsiveness.

- Genetics play a role. The alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency gene predisposes to early‑onset COPD, while the ADAM33 gene has been linked to asthma susceptibility.

- Air pollution (particulate matter, ozone) aggravates both conditions, especially in urban settings.

- Occupational exposures like silica, dust, or chemicals can trigger COPD and also act as irritants for asthmatics.

Understanding these shared triggers helps target prevention.

Key Differences in Pathophysiology

Even though the symptoms can look alike, the underlying mechanisms diverge. Below is a quick side‑by‑side comparison.

| Feature | COPD | Asthma | Overlap (ACOS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical onset age | 40+ years | Childhood‑early adulthood | Varies; often 40‑60 |

| Main cause | Smoking, pollutants | Allergens, irritants | Combined exposure |

| Reversibility (post‑bronchodilator) | < 12% FEV1 improvement | > 12% FEV1 improvement | Mixed; often 12‑15% |

| Inflammatory cells | Neutrophils, macrophages | Eosinophils, mast cells | Both neutrophils & eosinophils |

| Airway remodeling | Permanent loss of elasticity | Reversible thickening | Combination of both |

Diagnosing Overlap - What Tests Matter?

Doctors rely on a mix of history, physical exam, and objective testing. The cornerstone is spirometry, which measures the volume of air you can force out in one second (FEV1) and the total volume (FVC). Key diagnostic clues include:

- Post‑bronchodilator FEV1 improvement of 12% or more suggests an asthma component.

- Persistent reduced FEV1/FVC ratio (<0.70) points to COPD.

- Blood eosinophil count: >300 cells/µL often indicates benefit from inhaled steroids.

- Imaging (chest X‑ray or CT) can reveal hyperinflation in COPD and airway wall thickening in asthma.

Because symptoms overlap, a single test rarely tells the whole story. Physicians combine results to decide the best treatment plan.

Managing the Overlap - A Balanced Approach

Therapy needs to hit two birds: reduce chronic inflammation (an asthma trait) and keep the airways open (a COPD trait). The typical regimen looks like this:

- Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) help control eosinophilic inflammation. Low‑to‑moderate doses are usually enough if blood eosinophils are high.

- Long‑acting bronchodilators - a LABA (long‑acting beta‑agonist) or LAMA (long‑acting muscarinic antagonist) - maintain airway patency. Many guidelines recommend a combination LABA/LAMA for overlap patients.

- Short‑acting bronchodilators (SABA) are used for quick relief of flare‑ups.

- Vaccinations (influenza, pneumococcal) reduce infection‑related exacerbations.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation - exercise, breathing techniques, and education - dramatically improves quality of life.

For severe cases, oral steroids or biologic agents (e.g., anti‑IL‑5) may be considered, especially if eosinophil counts stay high despite inhaled therapy.

Lifestyle Tips to Protect Your Lungs

Even the best meds can’t fully offset unhealthy habits. Here are practical steps you can start today:

- Quit smoking - use nicotine replacement or prescription meds like varenicline. Within a year, lung function decline slows sharply.

- Avoid indoor pollutants: use HEPA filters, keep humidity below 60% to limit mold.

- Stay active - brisk walking or cycling improves cardiovascular fitness and helps keep airways clear.

- Monitor air quality - on high‑pollution days, limit outdoor exposure or wear a N95 mask.

- Follow an anti‑inflammatory diet rich in omega‑3s, fruits, and vegetables; studies link such diets to lower asthma exacerbations.

Remember, small changes add up, and many people see noticeable breathing improvements within weeks.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I have both COPD and asthma at the same time?

Yes. When features of both diseases appear, doctors label it asthma‑COPD overlap syndrome. It’s common in people over 40 who smoke or have long‑term exposure to pollutants.

Is asthma‑COPD overlap more severe than either condition alone?

Generally, yes. Overlap patients experience more frequent flare‑ups, faster lung‑function decline, and a higher risk of hospitalization. Early detection and a combined treatment plan can mitigate these risks.

Do inhaled steroids work for COPD?

Inhaled steroids are less effective for pure COPD, but they’re valuable when there’s an asthma component or high eosinophil count. That’s why blood work often guides therapy in overlap cases.

Can quitting smoking reverse COPD?

Quitting stops further damage and can improve symptoms, but existing structural changes remain. The goal becomes slowing progression rather than full reversal.

What tests confirm an overlap diagnosis?

Spirometry with bronchodilator response, blood eosinophil count, and sometimes a chest CT scan. Doctors also review symptom patterns, smoking history, and allergy testing.

Living with COPD, asthma, or both doesn’t have to mean constant breathlessness. By understanding the similarities and differences, staying ahead of triggers, and using a tailored medication mix, you can protect your lungs and enjoy a fuller, more active life.

Deepak Bhatia

October 1, 2025 AT 16:10Hey there, I really appreciate you breaking down the overlap between COPD and asthma. It can feel overwhelming when symptoms seem to blur, but this guide gives clear signs to watch for. If you notice a persistent cough along with wheezing, especially after years of smoking, it's a good idea to get a spirometry test. Remember, you don't have to face this alone – talk to your doctor and ask about inhaled therapies that can help. Small lifestyle changes like quitting smoking and using air purifiers can make a big difference. Stay hopeful, and keep an eye on those triggers.

Samantha Gavrin

October 15, 2025 AT 13:30While the article is helpful, the real story is hidden. Big pharma sponsors most of the research, pushing inhaled steroids to keep patients dependent on pricey meds. The overlap syndrome is often used as a marketing ploy to sell combination inhalers. Don't be fooled by the glossy brochures – look for independent studies and consider natural anti‑inflammatory options. Remember, the government quietly approves these drugs without full transparency.

NIck Brown

October 29, 2025 AT 09:50Honestly, this whole “overlap” hype is just a way for clinicians to sound sophisticated. The differences between COPD and asthma have been known for decades; you don’t need a fancy name to treat them. Most patients end up on a cocktail of bronchodilators and steroids whether they need it or not. Focus on real evidence: quit smoking, use pulmonary rehab, and avoid over‑medicating. Simpler is better.

Andy McCullough

November 12, 2025 AT 07:10From a pathophysiological standpoint, the asthma‑COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) represents a heterogeneous phenotype characterized by concurrent features of eosinophilic airway inflammation and neutrophil‑predominant chronic obstructive processes. First, spirometric assessment should document a post‑bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70 combined with an FEV1 improvement ≥12% and 200 mL, signifying reversible obstruction. Second, biomarkers such as peripheral blood eosinophil counts >300 cells/µL correlate with a favorable response to inhaled corticosteroids, while neutrophil‑driven sputum profiles suggest a greater role for long‑acting muscarinic antagonists. Third, imaging modalities-high‑resolution CT-can differentiate emphysematous changes typical of COPD from airway wall thickening seen in asthma. Fourth, therapeutic algorithms now advocate a triple inhaler regimen (ICS/LABA/LAMA) for patients with frequent exacerbations, acknowledging the synergistic benefit of anti‑inflammatory and bronchodilatory actions. Fifth, recent trials have demonstrated that biologic agents targeting IL‑5 or IgE can reduce exacerbation frequency in the subset of ACOS patients with elevated eosinophils, though cost‑effectiveness remains a limitation. Sixth, vaccination strategies (influenza, pneumococcal) are essential adjuncts, reducing infection‑driven exacerbations that disproportionately affect overlap patients. Seventh, pulmonary rehabilitation improves exercise tolerance and dyspnea scores, independent of pharmacologic therapy, by enhancing diaphragmatic efficiency and peripheral muscle conditioning. Eighth, smoking cessation, even after a COPD diagnosis, decelerates annual FEV1 decline by approximately 30 mL/year, underscoring the importance of nicotine‑replacement therapy and behavioral counseling. Ninth, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and anxiety/depression should be screened routinely, as they modify outcomes and therapeutic choices. Tenth, patient‑reported outcome measures, including the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and Asthma Control Test (ACT), provide valuable feedback for titrating therapy. Eleventh, adherence monitoring via electronic inhaler trackers can illuminate patterns of underuse, prompting targeted education. Finally, a multidisciplinary approach-integrating pulmonologists, allergists, primary care, and respiratory therapists-optimizes individualized care pathways for ACOS patients, ultimately improving quality of life and reducing healthcare utilization.

Zackery Brinkley

November 26, 2025 AT 04:30Great rundown, everyone! If you’re juggling both conditions, remember to keep a symptom diary – note when you’re short of breath, what you were doing, and any environmental triggers. This simple habit can help your doctor fine‑tune the inhaler combo and spot patterns you might miss. Also, don’t underestimate the power of breathing exercises; techniques like pursed‑lip breathing can ease airflow limitation in COPD, while diaphragmatic breathing calms asthma attacks. Keep pushing forward, you’ve got this.

Luke Dillon

December 10, 2025 AT 01:50Hey friend, just wanted to echo what Zackery said – a little bit of daily movement goes a long way. Even a short walk each day can improve lung capacity and mood. Pair it with a clean indoor environment – think HEPA filters and low‑humidity to cut mold. And don’t forget your inhalers – keep them handy and check the expiration dates. You’re doing great, keep at it!

Elle Batchelor Peapell

December 23, 2025 AT 23:10Isn't it wild how our lungs can be both stubborn and generous? They hold onto every breath like a secret, yet they betray us when the air gets rough. Thinking about overlap feels like a metaphor for life – we carry multiple stories at once, sometimes clashing, sometimes harmonizing. Maybe the key is listening to each whisper, not just the loud coughs. Stay curious.

Jeremy Wessel

January 6, 2026 AT 20:30Breathing well is a choice.

Laura Barney

January 20, 2026 AT 17:50Wow, this post paints a vivid picture of the tangled web of lung disease! The colors of inflammation, the dance of medication – it’s all so striking. I love how you highlighted the lifestyle tweaks; they’re the brushstrokes that finish the masterpiece. Keep the palette fresh, and we’ll all breathe easier.

Jessica H.

February 3, 2026 AT 15:10The article presents a thorough overview, yet it neglects to address the socioeconomic barriers that impede access to optimal therapy. Many patients cannot afford combination inhalers, and the piece fails to propose realistic alternatives. Moreover, the language, while generally clear, occasionally lapses into vague generalities that might confuse lay readers. A more nuanced discussion of health equity would strengthen the argument.

Tom Saa

February 17, 2026 AT 12:30In the grand scheme, our respiratory system mirrors the paradox of existence: both fragile and resilient. We inhale hope, exhale doubt, and sometimes the air we draw is clouded by unseen forces. Contemplating the overlap, we see the intertwining of our physical and metaphysical realms.

John Magnus

February 22, 2026 AT 03:37From a clinical pharmacology perspective, the ACOS phenotype mandates a precision‑medicine approach. Initiate high‑dose inhaled corticosteroids if eosinophil counts exceed 300 cells/µL, then titrate LABA/LAMA based on bronchodilator responsiveness. Monitor biomarkers quarterly to avoid overtreatment and steroid‑related adverse effects. Aggressive step‑up therapy is justified in patients with ≥2 exacerbations per year, but always balance risk versus benefit.