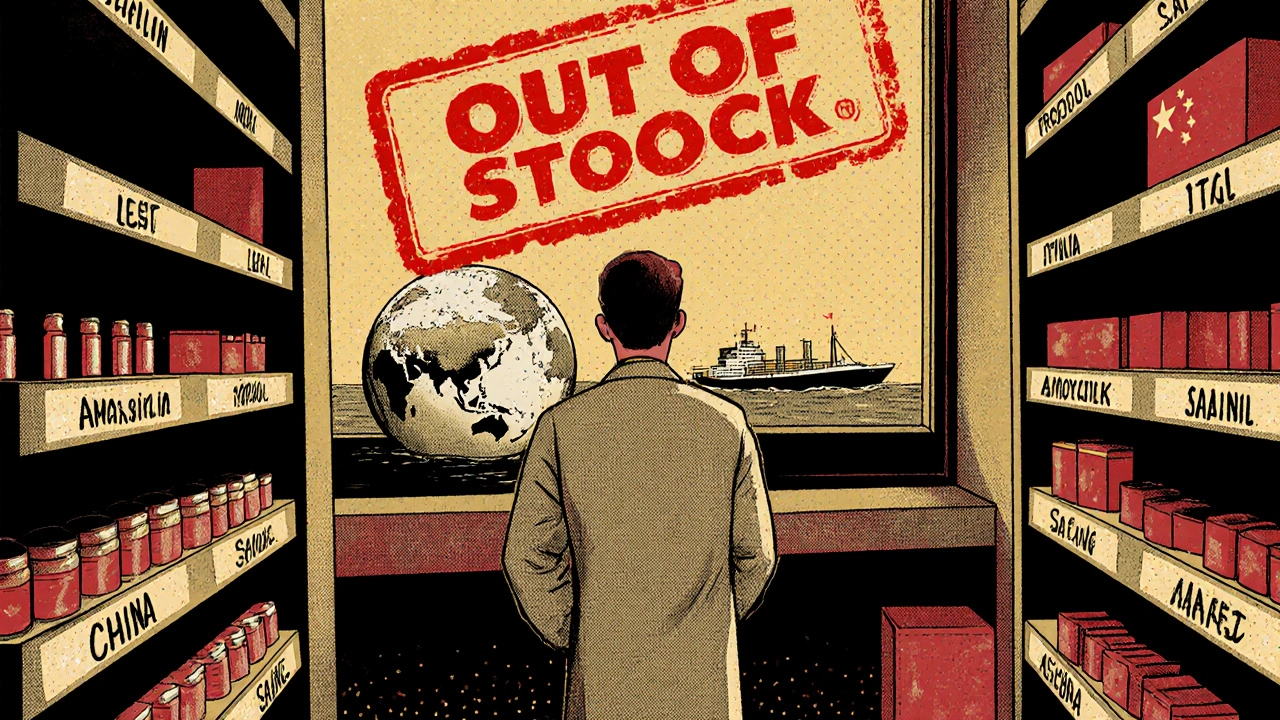

Every year, hundreds of essential generic drugs disappear from hospital shelves and pharmacy counters. These aren’t rare specialty medications-they’re the basics: antibiotics like amoxicillin, chemotherapy drugs like doxorubicin, anesthetics like propofol, and even saline IV bags. When they vanish, patients suffer. Doctors scramble. Nurses spend hours tracking down alternatives. And the root of the problem isn’t a single mistake-it’s a broken system built on thin margins, global dependencies, and zero room for error.

Manufacturing Failures Are the Top Cause

More than half of all generic drug shortages-62% according to the FDA-come down to one thing: manufacturing problems. It’s not about running out of raw materials. It’s about factories failing inspections, equipment breaking down, or contamination shutting down entire production lines.

Imagine a single facility in India or China that makes 70% of the world’s supply of a critical antibiotic. One fungal contamination in a sterile injectable line means every hospital in the U.S. that relies on that drug suddenly has nothing. The FDA can’t just wave a wand and fix it. The company has to stop production, clean everything, retest, reinspect, and wait weeks or months for approval to restart. During that time, there’s no backup. No spare parts. No extra stock.

These aren’t new factories with cutting-edge tech. Most are aging facilities running old equipment, squeezing out profits by minimizing maintenance. Why? Because the profit margins on generic drugs are often below 15%. Compare that to branded drugs, which can make 30-40%. When you’re barely breaking even, you don’t invest in redundancy. You cut costs. And that’s exactly when things break.

Zero Buffer, Zero Safety Net

Unlike car manufacturers who keep spare parts on hand, or grocery stores that stock extra cans of soup, pharmaceutical companies operate with next-to-no excess capacity. That’s by design. Why pay to run extra machines or keep extra inventory when you’re selling a drug for pennies?

This ‘just-in-time’ model works fine-until it doesn’t. A power outage in a Chinese API plant. A shipping delay at a port. A quality control failure in a U.S. facility. Any single hiccup becomes a nationwide crisis because there’s no buffer. No safety net. No spare tires.

One study found that one in five shortage reports involve a drug made by only one manufacturer. No alternatives. No competition. Just one plant, one line, one chance. When that fails, patients go without.

Global Supply Chains Are Too Concentrated

Eighty percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in U.S. generic drugs come from just two countries: China and India. That’s not a coincidence. It’s economics. Labor is cheaper. Regulations are looser. And companies have been chasing lower costs for decades.

But that concentration creates a single point of failure for the entire system. A flood in a Chinese chemical plant. A labor strike in an Indian facility. A trade dispute. A pandemic lockdown. Any of these can ripple across the globe and leave American hospitals empty.

And it’s not just about where the ingredients come from-it’s about where the final products are made. Nearly half of all finished drug manufacturing facilities in the U.S. are overseas. That means even if a drug is labeled “Made in the USA,” the core ingredient might have traveled halfway around the world, passed through multiple middlemen, and been stored in conditions outside U.S. oversight.

Profit Margins Are Too Low to Sustain Production

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. That’s the whole point. But the system has gone too far. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-the middlemen who negotiate drug prices for insurers-have pushed prices so low that some manufacturers can’t make money.

Three PBMs control about 85% of prescription drug spending in the U.S. They demand the lowest possible price. Manufacturers respond by cutting costs: fewer staff, less maintenance, slower quality checks. Some stop making the drug entirely. Between 2010 and 2023, over 3,000 generic products were discontinued. Many were low-margin, high-volume drugs that hospitals rely on daily.

When a drug’s profit margin drops below 5%, it becomes financially irrational to keep producing it-even if it’s in shortage. Why spend millions upgrading a line to meet FDA standards for a drug that earns you $0.02 per pill? The market doesn’t reward quality. It punishes it.

Purchasing Power Is Too Concentrated

It’s not just PBMs. The entire supply chain is dominated by a few big players. Hospitals buy from a handful of wholesalers. Wholesalers rely on a handful of manufacturers. Manufacturers depend on a handful of API suppliers.

This consolidation means there’s no competition to drive innovation or resilience. If one manufacturer quits, there’s no incentive for another to step in. Why invest millions to enter a market where the price is already crushed? The result? Fewer companies making more drugs. Fewer options when things go wrong.

And it’s not just about price. PBMs also control which drugs get listed on formularies. Sometimes, a drug that’s in adequate supply gets excluded because a cheaper, similar drug is in shortage. That forces doctors to use the shortage drug, even when it’s not available. It’s a perverse incentive that makes the problem worse.

Lack of Transparency Makes Everything Harder

One in four drug shortage reports in the U.S. don’t even list a reason. No explanation. No timeline. No visibility.

Hospitals call manufacturers. Manufacturers say, “We can’t tell you.” Why? Because they’re afraid of legal liability. Because they’re waiting for FDA approval. Because they’re not required to disclose anything until it’s too late.

Meanwhile, pharmacists spend 50-75% more time managing shortages than they did a decade ago. They’re calling other hospitals, checking alternate suppliers, scrambling for substitutes. Nurses are rationing doses. Patients are getting delayed cancer treatments. These aren’t theoretical problems-they’re happening right now, every day.

Canada Does It Better-Here’s How

Canada faces the same global supply chain risks. Same manufacturers. Same APIs. Same low margins. But they have fewer shortages.

Why? Because they coordinate. Health systems, regulators, wholesalers, and manufacturers talk to each other. They share data. They build stockpiles-not just for bioterrorism, but for everyday drug shortages. They have a national alert system. They incentivize production of low-margin drugs.

In the U.S., the Strategic National Stockpile exists only for disasters like pandemics or attacks. It doesn’t hold antibiotics or IV fluids for routine shortages. Canada’s system is designed for daily healthcare needs. The U.S. system is designed for emergencies that rarely happen.

What’s Being Done? Not Enough.

There are proposals. The RAPID Reserve Act (S.2510/H.R.6802) aims to create a federal stockpile of critical generic drugs. The FTC is investigating PBMs for anti-competitive behavior. The AMA wants to stop formularies from excluding drugs that are actually in stock.

But these are fixes to symptoms, not causes. The core problem remains: we’ve built a system that rewards the lowest price over the most reliable supply. We’ve outsourced production to countries with weak oversight. We’ve eliminated competition. We’ve removed accountability.

Until we change the economics-until we pay manufacturers enough to invest in quality, redundancy, and resilience-we’ll keep seeing the same headlines: ‘Drug Shortage Hits Hospitals.’ And patients will keep paying the price.

Linda Rosie

November 24, 2025 AT 10:43Every time I see a shortage of amoxicillin, I think about how we treat medicine like toilet paper-buy it cheap, use it up, and never think about where it came from.

It’s not rocket science. We just refuse to pay for reliability.

Vivian C Martinez

November 24, 2025 AT 23:41This is one of those issues where the solution is obvious but politically inconvenient.

Investing in domestic manufacturing capacity, creating strategic reserves for essential generics, and regulating PBMs aren’t radical ideas-they’re basic public health responsibilities.

We’ve done it for vaccines, for blood supplies, for PPE. Why not for antibiotics and IV fluids?

The cost of inaction isn’t just financial-it’s measured in lives delayed, treatments canceled, and families terrified.

Ross Ruprecht

November 26, 2025 AT 23:27Ugh, another ‘the system is broken’ essay. Can we just fix the FDA? They’re the ones dragging their feet on inspections.

Stop blaming capitalism and fix the bureaucracy.

Lisa Lee

November 27, 2025 AT 21:28Of course Canada does it better. We actually treat healthcare like a right, not a profit margin.

You outsourced your medicine to cheap labor and now you’re surprised when it breaks?

Stop pretending this is a ‘supply chain issue.’ It’s a moral failure.

And no, your ‘RAPID Reserve Act’ won’t fix anything until you stop letting PBMs dictate prices like dictators.

Pramod Kumar

November 28, 2025 AT 06:23Let me tell you something from the other side of the globe-when a factory in India shuts down for a fungal contamination, it’s not just a ‘supply chain hiccup’ for you.

It’s a month of lost wages for the workers, a year of debt for the owner, and a quiet panic in the community that feeds on that factory’s payroll.

We don’t make drugs to be ‘cheap’-we make them because it’s the only way to feed our families.

And when your FDA shuts us down for a speck of mold, you don’t see the kids who miss school because their dad can’t work.

It’s easy to lecture from your office in D.C., but the real cost? It’s paid in sweat, silence, and stolen sleep.

Maybe the answer isn’t just more stockpiles-it’s respect.

Respect for the hands that make your pills.

Respect for the systems that keep them running.

Respect for the fact that we’re all in this together-even if your pharmacy shelves make you forget it.

Brandy Walley

November 28, 2025 AT 22:54lol why do we even have hospitals if we cant just order more drugs off amazon?

someone should just make a generic drug amazon prime subscription

problem solved

also pbms are evil but so is the government

why cant we just print money and call it medicine

jk unless?

wait no im serious

shreyas yashas

November 30, 2025 AT 20:29My cousin works at a pharma plant in Hyderabad. They got shut down last year for a tiny mold issue-same thing they’re talking about.

They spent six months fixing it, lost 80% of their clients, and now they’re barely hanging on.

Meanwhile, the same drug is sold for 3x the price in the US because ‘supply chain costs’.

It’s not broken-it’s rigged.

And the people who pay the price? They’re not on the boardroom calls.

They’re the ones waiting for chemo.

And yeah, I know nobody wants to hear this.

But someone’s gotta say it.

Katy Bell

December 2, 2025 AT 14:58I worked in oncology nursing for 12 years.

There was a time we had to split single vials of doxorubicin between two patients because the next shipment was ‘delayed indefinitely.’

We used syringes with milligram precision. We weighed doses on scales calibrated to the tenth of a microgram.

And we cried in the supply closet.

Not because we were weak.

Because we were human.

And this system? It doesn’t just fail patients.

It breaks the people trying to save them.

Every time.