Every year, thousands of people undergoing cancer treatment or immune therapy for autoimmune diseases face a silent threat: HBV reactivation. It doesn’t come with warning signs until it’s too late - sudden jaundice, extreme fatigue, liver failure. And here’s the kicker: it’s almost always preventable.

What Exactly Is HBV Reactivation?

HBV reactivation happens when a dormant hepatitis B virus wakes up. Most people who’ve had hepatitis B in the past clear the virus, but the viral DNA hides in their liver cells. It’s not active. It’s not causing harm. Then comes chemotherapy, a biologic drug like rituximab, or a stem cell transplant - and suddenly, the immune system is knocked down. The virus takes advantage. It starts replicating fast. The liver gets attacked. ALT and AST levels spike. In severe cases, patients go into acute liver failure - and die.

This isn’t rare. In patients who are HBsAg-positive (meaning they’re still carrying the virus), reactivation rates can hit 73% if they get anti-CD20 drugs like rituximab. Even in those who think they’re “cured” - HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive - the risk is still 10-18% with strong immunosuppressants. And if you don’t catch it early, the fatality rate is 5-10%.

Which Treatments Are the Biggest Risks?

Not all immunosuppressive drugs are created equal. Some are low-risk. Others are landmines.

- High-risk (38-81% reactivation): Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (rituximab, ofatumumab), anthracycline chemo (like doxorubicin), and stem cell transplants - especially allogeneic ones. In one study, 81% of allogeneic transplant patients had HBV reactivation within two years.

- Intermediate-risk (1-10%): Conventional chemo without steroids, TNF-alpha inhibitors (like infliximab), and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib).

- Low-risk (under 1%): Most non-cytotoxic targeted therapies and non-TNF biologics.

Here’s the twist: even radiation therapy can trigger reactivation. A 2020 study found a 14% reactivation rate in HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive liver cancer patients after radiation. And checkpoint inhibitors? They’re a newer danger. In HBsAg-positive patients not on antivirals, 21% had reactivation - even when their viral load was undetectable before treatment.

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for liver tumors? Turns out, it’s riskier than we thought - 17.5% to 33.7% reactivation. That’s higher than many chemo regimens.

Who’s at Risk? The Serology Breakdown

You can’t guess who’s at risk. You have to test.

There are three key markers:

- HBsAg-positive: Active infection. Highest risk. Reactivation rates from 20% to over 80% depending on therapy.

- HBsAg-negative / anti-HBc-positive: Past infection. Virus hidden. Still at risk - especially with high-dose chemo or biologics. Reactivation risk: 1% to 18%.

- Anti-HBs-positive: Immune from vaccine or past infection. Very low risk - under 0.5%.

Many doctors still assume if someone’s HBsAg-negative, they’re safe. That’s a deadly mistake. In one case report, a 52-year-old lymphoma patient died from HBV reactivation after rituximab - because no one checked his anti-HBc status.

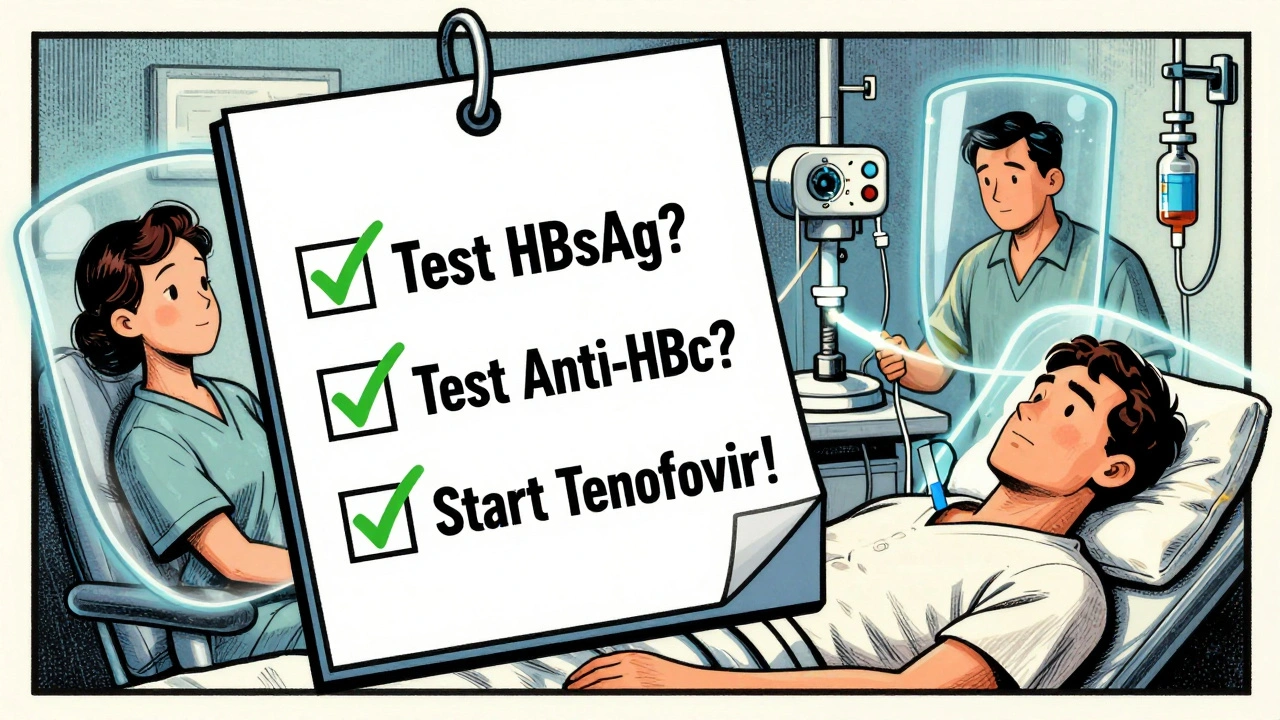

How to Prevent It: Screening and Prophylaxis

Prevention is simple, cheap, and life-saving.

Step 1: Screen everyone. Before any immunosuppressive therapy - whether it’s for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, or Crohn’s - test for HBsAg and anti-HBc. That’s it. No exceptions. The cost? Less than $50. The risk of not doing it? Death.

Step 2: If positive, start antivirals before treatment. For HBsAg-positive patients, begin tenofovir or entecavir at least one week before chemo or biologics. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t wait for viral load to rise. Start early.

Step 3: Keep the antiviral going after treatment. For high-risk therapies, continue antivirals for at least 6-12 months after therapy ends. A 2022 NEJM study showed 6 months is enough for most cases - a big shift from older guidelines that pushed for a full year.

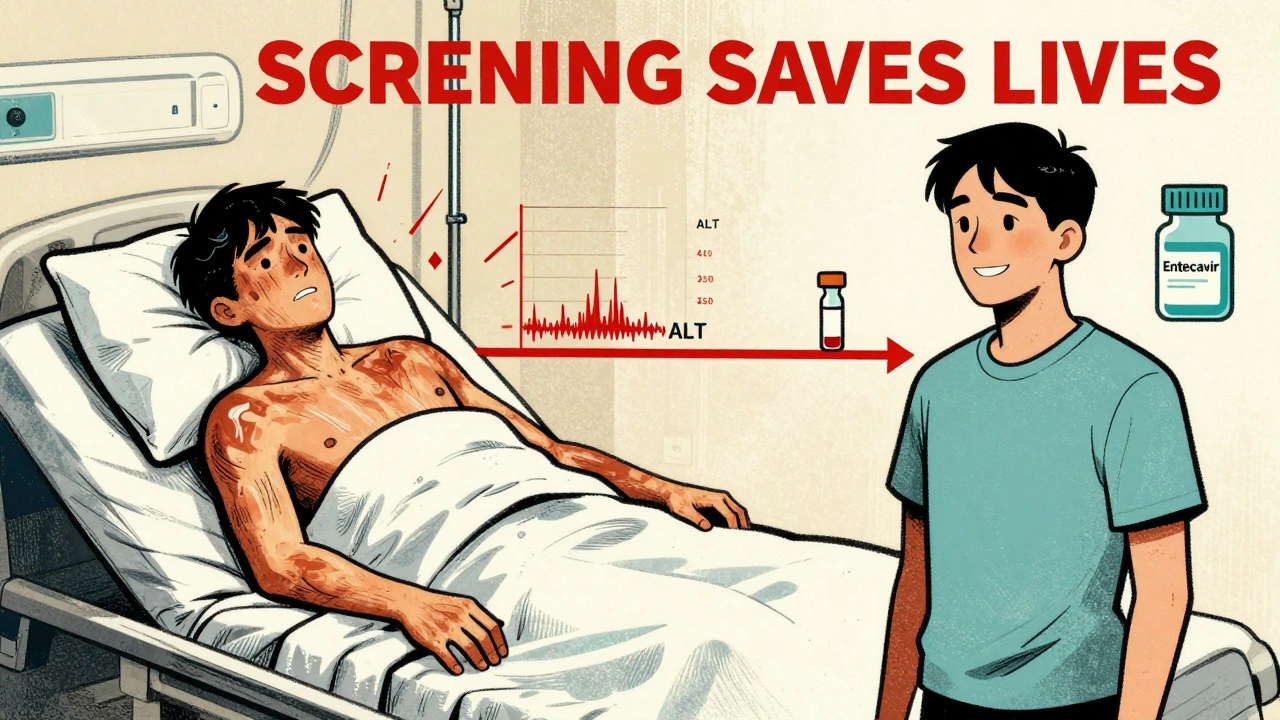

One study of 1,245 HBsAg-positive patients found that those on prophylaxis had only a 3.2% reactivation rate. Those without? 48.7%. That’s a 93% reduction in risk.

Why Don’t More Doctors Do This?

Because it’s not always part of the workflow.

A 2020 survey showed only 58% of community oncologists follow screening guidelines. At academic hospitals? 89%. Why the gap? Lack of systems. No automated alerts in electronic records. No clear protocols. Nurses aren’t trained. Doctors assume someone else checked.

One hospital in California fixed it by adding mandatory HBV screening alerts in their EHR. Before: 12.3% reactivation rate. After: 1.7%. That’s not magic. That’s a checklist.

Another problem: we’re overtreating. About 30% of people screened are low-risk - they get antivirals unnecessarily. But that’s still better than missing one high-risk patient.

What About Newer Drugs? Checkpoint Inhibitors and Beyond

Immunotherapy is changing cancer care - but it’s also changing HBV risk.

Drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitors) can trigger immune-related hepatitis. That looks just like HBV reactivation. But the treatment is totally different. One mistake - giving steroids for what you think is immune hepatitis - can make HBV reactivation worse.

That’s why testing is non-negotiable. If you’re on a checkpoint inhibitor and you’re HBsAg-positive? Start antivirals before you start the drug. Even if your viral load is undetectable. The 2021 ESMO guidelines now say this outright.

The Bottom Line: Don’t Wait for Symptoms

HBV reactivation is not a curiosity. It’s a preventable emergency. Every patient getting chemotherapy, biologics, or even radiation for cancer needs a simple blood test before treatment starts. If they’re HBsAg-positive or anti-HBc-positive - give them tenofovir or entecavir. Don’t wait. Don’t assume. Don’t hope.

The data is clear. Screening and prophylaxis cut reactivation risk from nearly 50% to under 5%. That’s not just good medicine. It’s lifesaving medicine.

And if your doctor hasn’t mentioned it? Ask. Say: “Have you checked my HBV status before starting this treatment?” If they don’t know - get a second opinion.

What Happens If You Skip Screening?

Here’s what real patients have faced:

- A 45-year-old woman with lymphoma started rituximab without screening. Three weeks later, she was in liver failure. Died within 10 days.

- A 68-year-old man with rheumatoid arthritis on infliximab developed jaundice. His ALT was 1,200. Turned out he had past HBV. He survived - but only because his wife insisted on a liver panel.

- A 31-year-old with Crohn’s disease got adalimumab. No screening. He developed fulminant hepatitis. Needed a transplant.

These aren’t outliers. They’re preventable tragedies.

What is HBV reactivation?

HBV reactivation is when the hepatitis B virus, which was dormant in the liver, suddenly starts replicating again because the immune system is weakened by chemotherapy, biologics, or other immunosuppressive treatments. This can cause severe liver damage, acute hepatitis, and even liver failure if not treated early.

Who needs to be screened for HBV before treatment?

Everyone starting immunosuppressive therapy - including chemotherapy, biologics like rituximab, stem cell transplants, and even some radiation therapies - should be screened. That means testing for HBsAg and anti-HBc, regardless of age, symptoms, or perceived risk. Even people who think they’ve recovered from hepatitis B need this test.

What are the most dangerous drugs for triggering HBV reactivation?

Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies like rituximab and ofatumumab carry the highest risk - up to 73% in HBsAg-positive patients. Anthracycline chemotherapy (e.g., doxorubicin) and stem cell transplants - especially allogeneic - are also very high risk. Checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab can also trigger reactivation, even in patients with undetectable HBV DNA.

What antivirals are used for prophylaxis?

Tenofovir and entecavir are the two most effective antivirals for preventing HBV reactivation. They’re taken orally, have minimal side effects, and are highly effective. Treatment should start at least one week before immunosuppressive therapy begins and continue for 6 to 12 months after treatment ends, depending on the drug and patient risk.

Can you skip screening if you’ve been vaccinated?

Yes - if you’re anti-HBs-positive, meaning you have protective antibodies from vaccination or past infection, your risk is extremely low (under 0.5%). Screening isn’t needed for these patients. But if you’re unsure of your vaccination status or have never been tested, it’s safer to screen than to assume.

What happens if you miss the screening?

If screening is skipped and HBV reactivation occurs, the consequences can be severe - including acute liver failure, need for transplant, or death. Case fatality rates range from 5% to 10% in untreated cases. Many of these deaths are preventable with simple blood tests and early antiviral treatment.

Is HBV prophylaxis expensive?

No. Tenofovir and entecavir are generic and cost less than $10 per month in most countries. Screening costs under $50. Compared to the cost of hospitalization for liver failure - which can exceed $100,000 - prophylaxis is one of the most cost-effective interventions in modern medicine.

Why don’t all doctors screen patients?

Many community practices lack automated systems to remind providers to test. Some assume patients are low-risk or that someone else already checked. Others are unaware of updated guidelines. Studies show only 58% of community oncologists follow screening protocols, compared to 89% in academic centers.

How long should antiviral prophylaxis last?

For high-risk therapies like rituximab or stem cell transplant, antivirals should continue for at least 6 months after treatment ends. For some patients, especially those with ongoing immune suppression, 12 months may be recommended. A 2022 NEJM study showed 6 months is sufficient for most cases, which has changed clinical practice.

Can HBV reactivation happen after cancer treatment is done?

Yes. Reactivation can occur weeks or months after chemotherapy or biologics end, especially if antivirals are stopped too early. That’s why continuing prophylaxis for 6-12 months after treatment is critical - even if the patient feels fine.

Gilbert Lacasandile

December 10, 2025 AT 05:51Just had a patient come through last week with this exact scenario-HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive, started rituximab for lymphoma. No screening. Three weeks in, ALT hit 2,100. They barely made it to transplant. This post? It’s not just important-it’s a lifeline. Why are we still treating this like an afterthought?

Lola Bchoudi

December 11, 2025 AT 18:13As a hepatology nurse coordinator, I’ve seen the chaos unfold when prophylaxis is delayed. The key is timing: tenofovir must be initiated ≥7 days pre-immunosuppression. Waiting for viral load to rise? That’s like waiting for the fire to spread before calling 911. Our hospital implemented mandatory EHR alerts-reactivation rates dropped from 14% to 1.2% in 18 months. Simple systems save lives.

Morgan Tait

December 12, 2025 AT 09:54Let’s be real-this isn’t about medicine. It’s about control. Big Pharma doesn’t want you screening everyone because then they’d have to sell you $10/month antivirals instead of $50,000 liver transplants. And don’t get me started on how the CDC ignores this because it’s ‘too niche.’ But hey, if you’re a rich white guy in Boston, your doc checks your HBV status. If you’re a single mom in rural Alabama? Good luck. This is healthcare apartheid dressed up as protocol.

Katie Harrison

December 12, 2025 AT 23:56Thank you for this. In Canada, we’re starting to catch up-Ontario now mandates HBV screening for all oncology referrals. But rural clinics? Still flying blind. I’ve had patients tell me their oncologist said, ‘You’re young, you’re healthy, you’re fine.’ No. No, you’re not. This isn’t about risk-it’s about biology. Screening isn’t optional. It’s non-negotiable.

Mona Schmidt

December 14, 2025 AT 14:17One detail often overlooked: anti-HBs titers. If a patient has detectable anti-HBs (>10 mIU/mL), reactivation risk is negligible-even if anti-HBc-positive. But many labs don’t report titers, only positivity. Clinicians then assume ‘past infection = risk.’ That’s inaccurate. We need labs to report quantitative anti-HBs alongside HBsAg and anti-HBc. Otherwise, we’re overtreating 20-30% of patients unnecessarily. Precision matters.

Guylaine Lapointe

December 16, 2025 AT 09:00Wow. Just… wow. So we’re supposed to believe that doctors are just ‘forgetting’ to screen? That’s not negligence-it’s malpractice. And yet, no one gets fired. No one gets sued. No one even gets a slap on the wrist. Meanwhile, people die. Quietly. Alone. In hospital beds. Because someone didn’t check a box. This isn’t a medical issue. It’s a moral failure.

Sarah Gray

December 18, 2025 AT 03:28How can you possibly trust a system where 42% of community oncologists ignore guidelines? You can’t. This isn’t just about HBV-it’s about the collapse of clinical diligence. If we can’t get basic viral screening right, how can we possibly manage immunotherapy toxicity, CAR-T complications, or genomic-guided therapy? The entire house of cards is crumbling. And the worst part? The people who need this most can’t even afford to demand it.

Graham Abbas

December 18, 2025 AT 06:40There’s something deeply human here. We treat cancer like a war-brutal, urgent, all-consuming. But we treat the liver like an afterthought. A silent organ. A bystander. And yet, it’s the one that dies first when we forget it. Maybe we don’t fear the virus. Maybe we fear our own indifference. We know the test. We know the drug. We know the timeline. And still-we wait. We assume. We hope. And then we mourn. Not because we didn’t know. But because we chose not to act.