How Hospitals Decide Which Generic Drugs to Stock

Every pill, injection, and capsule in a hospital isn’t just picked because it’s cheap or available. There’s a strict, science-backed process behind every drug on the shelf. This system is called a hospital formulary-a living list of approved medications that hospitals use to balance safety, effectiveness, and cost. And when it comes to generic drugs, the stakes are high: they make up 90% of prescriptions but only 26% of drug spending in U.S. hospitals.

So how do hospitals pick which generics to include? It’s not about who offers the lowest price. It’s not even just about FDA approval. It’s a slow, careful, committee-driven process that involves doctors, pharmacists, economists, and real-world data. And it changes constantly.

The Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee: The Real Decision-Makers

Behind every formulary is a group called the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee. These aren’t administrative staff. They’re clinical experts-board-certified pharmacists, physicians, and sometimes healthcare economists. Most committees have 12 to 15 members. They meet monthly or quarterly to review new drug requests and reassess existing ones.

When a hospital wants to add a new generic drug-say, a cheaper version of a blood pressure medication-the process starts with a formal request. The requester must submit a dossier: clinical trial data, pharmacokinetic studies, side effect profiles, and comparisons to existing formulary drugs. The FDA’s Orange Book confirms bioequivalence (the generic must deliver 80-125% of the active ingredient compared to the brand), but that’s just the starting line.

Then comes the real work: reviewing at least 15-20 peer-reviewed studies on efficacy and safety. Not just one or two flashy papers. Real systematic reviews. If the drug has a higher rate of adverse events in the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System, it gets flagged-even if it’s 30% cheaper.

Cost Isn’t Just the Price Tag

Many assume hospitals pick generics because they’re cheap. That’s true-but only partially. The real metric is total cost of care. A cheaper pill might lead to more readmissions, longer hospital stays, or more emergency visits if it’s poorly absorbed or causes side effects.

For example, two generic versions of warfarin might cost the same per pill. But one comes in a tablet that’s harder for elderly patients to swallow. That leads to missed doses. Missed doses mean more INR checks, more clinic visits, more bleeding events. That’s not saving money-it’s costing more.

Hospitals now use predictive analytics to model these downstream costs. A 2023 KLAS Research report found 61% of hospitals track how a drug choice affects length of stay, readmission rates, and lab utilization. One hospital in Ohio saved $1.2 million a year by switching to a formulary-preferred generic anticoagulant-not because it was the cheapest, but because patients stayed out of the ER.

Tiers, Substitutions, and the Rules of Engagement

Hospital formularies are usually split into three to five tiers. Generic drugs sit in Tier 1-lowest cost to the patient, lowest barrier for prescribers. But here’s the twist: hospitals don’t just list drugs. They control access.

Most U.S. hospitals use a closed formulary. That means if a drug isn’t on the list, it’s not routinely stocked. A doctor can still order it, but they need prior authorization-a paperwork hurdle that often delays care. A 2021 AMA survey found 32% of physicians felt formulary restrictions directly hurt patient outcomes.

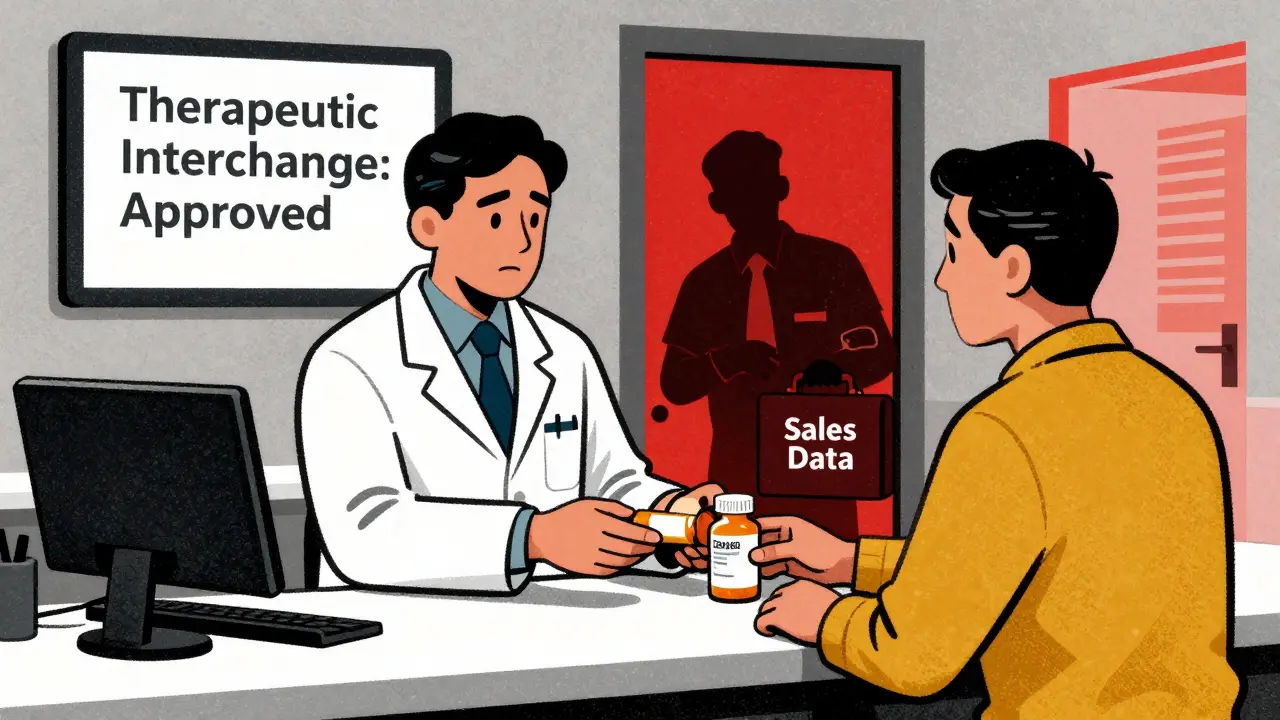

But pharmacists have power too. In therapeutic interchange programs, a pharmacist can swap a non-formulary generic for a formulary-approved one at the pharmacy counter-without asking the doctor. This works well for conditions like hypertension, where 92% of ACE inhibitor prescriptions are already generic. But it causes friction. A 2022 American Pharmacists Association survey found 57% of pharmacists have had arguments with doctors over substitutions.

The Hidden Problems: Supply Chains and Staffing Chaos

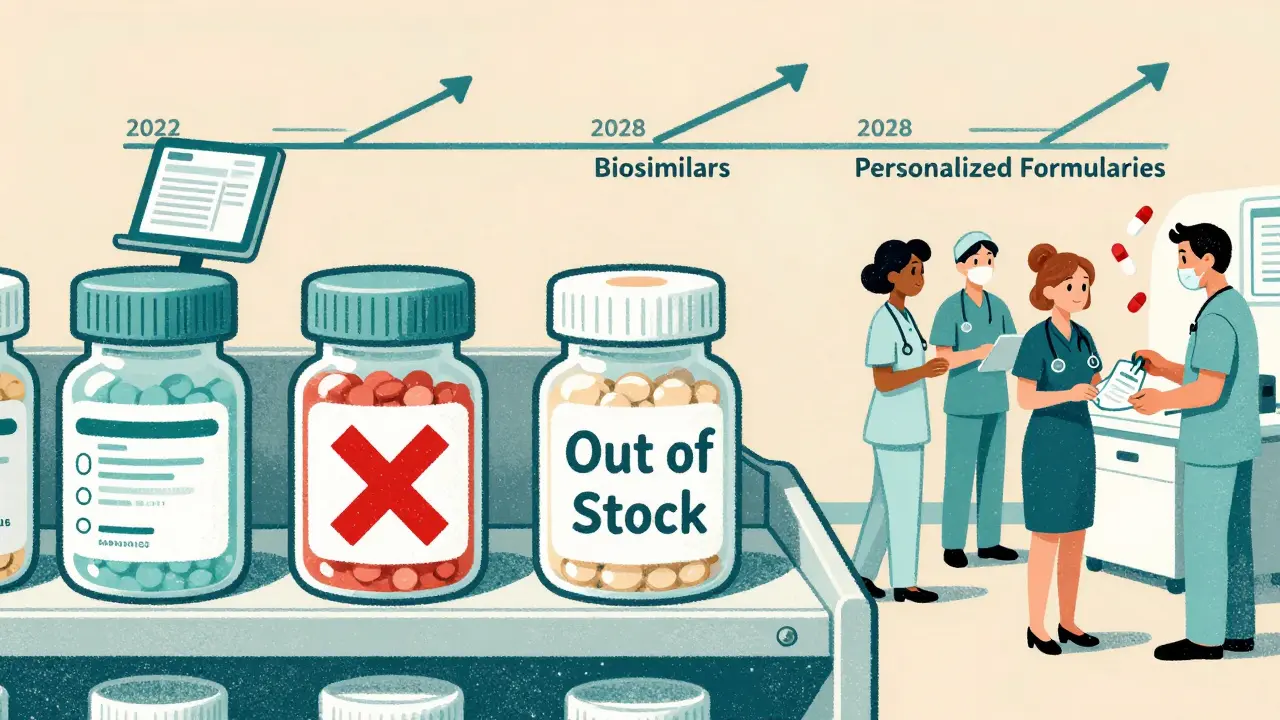

Even the best formulary can break down. In 2022, 268 generic drugs faced shortages in the U.S. That’s not rare. It’s routine. When a preferred generic runs out, hospitals scramble. Some temporarily remove it from the formulary. Others activate emergency alternatives.

At Massachusetts General Hospital, pharmacists had to suspend formulary status for seven different generics in one year due to supply issues. Each change meant retraining nurses, updating electronic health records, and explaining new packaging to patients. One nurse on AllNurses.com wrote: “We had a medication error because we gave the wrong generic after a formulary switch. Took three weeks to get back to normal.”

And it’s not just about drugs. It’s about people. Nurses and pharmacists are the ones who have to implement these changes. If they’re not trained, if the new pill looks different, if the dosing schedule changed-errors happen. That’s why training on conflict of interest and proper substitution is now mandatory for all P&T committee members in ASHP-accredited programs.

Who’s Influencing the List?

It’s not just clinical data driving decisions. Independent groups like the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) now provide cost-effectiveness analyses that 65% of large hospitals use. Their reports weigh clinical benefit against price, helping committees decide if a drug is worth the cost.

But there’s also pressure from the other side. Pharmaceutical reps still visit hospitals. A 2021 JAMA Internal Medicine study showed detailing by drug companies remains a documented barrier to objective formulary decisions-even when conflict of interest disclosures are required.

Some hospitals now ban drug reps from P&T meetings. Others require all submitted data to come from public sources only. Johns Hopkins, for example, uses only FDA and peer-reviewed data in its reviews-no company-sponsored studies.

The Future: Personalized Formularies and Biosimilars

The next frontier? Personalization. Eighteen percent of academic medical centers are now testing pharmacogenomic data in formulary decisions. If a patient has a gene variant that makes them metabolize a drug too slowly, the formulary might block certain generics and only allow ones with better safety profiles for that genotype.

Biosimilars-generic versions of complex biologic drugs-are another challenge. Only 37% of hospitals have formal protocols to evaluate them. Unlike simple chemical generics, biosimilars aren’t identical. They’re “highly similar.” That means more testing, more monitoring, more risk. Hospitals are moving slowly, but they’re moving.

And with the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act forcing Medicare Part D to align with hospital formulary standards by 2025, the pressure to standardize and optimize is growing. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality predicts formularies will become mandatory for all Medicare-certified facilities by 2028.

Why This Matters to Patients

You might never see the formulary. But you feel it. When your doctor prescribes a generic, it’s not random. It’s chosen because it’s been vetted by a team of experts who looked at hundreds of data points. It’s chosen because it’s safe, effective, and saves the system money-money that helps keep your hospital running.

But it’s also why sometimes you get a different pill than last time. Or why your insurance says you need paperwork to get your usual drug. It’s not bureaucracy for bureaucracy’s sake. It’s a system trying to do the right thing: give you the best possible care without wasting resources.

For every dollar saved on a generic pill, there’s a story behind it-clinical trials, committee debates, supply chain headaches, nurse training sessions. And every time it works, someone gets better faster. That’s the goal.

What is a hospital formulary?

A hospital formulary is an official, continuously updated list of medications approved for use within a healthcare system. It’s developed and managed by a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee using clinical evidence, safety data, and cost-effectiveness analysis. Only drugs on the formulary are routinely stocked and prescribed unless special approval is granted.

How are generic drugs chosen over brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs are selected when they meet FDA bioequivalence standards (80-125% absorption compared to the brand) and demonstrate equivalent clinical outcomes in peer-reviewed studies. Hospitals prioritize them because they offer the same therapeutic benefit at a fraction of the cost-often 80-90% cheaper. But cost alone doesn’t decide inclusion; safety, dosing convenience, and impact on patient adherence are weighed just as heavily.

Do hospitals ever reject generic drugs that are FDA-approved?

Yes. FDA approval only confirms bioequivalence. Hospitals look deeper. If a generic has a higher rate of adverse events in real-world data, causes more patient non-adherence due to pill size or frequency, or comes from a manufacturer with frequent supply issues, it can be rejected-even if it’s technically approved. For example, a generic version of levothyroxine might be pulled from the formulary if it’s linked to inconsistent thyroid levels in multiple patients.

Who makes the final decision on which drugs go on the formulary?

The Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee makes the final decision. This group includes pharmacists (often board-certified in pharmacotherapy), physicians (including specialists like cardiologists or infectious disease experts), and sometimes healthcare economists. Nurses and administrators may provide input, but the committee holds voting authority. Decisions are based on evidence-not sales pitches or convenience.

Why do I sometimes get a different generic version of the same drug?

Hospitals rotate generic suppliers based on cost, supply reliability, and clinical performance. If one manufacturer has a shortage or quality issue, the formulary may switch to another approved generic. This is done to ensure continuous availability. While the active ingredient is the same, differences in inactive ingredients (fillers, coatings) can affect how the drug is absorbed-especially in sensitive patients. Pharmacists monitor these changes closely to avoid adverse effects.

Can doctors prescribe drugs not on the formulary?

Yes, but it’s harder. Prescribing a non-formulary drug requires prior authorization-a process where the doctor must justify why the formulary-approved alternatives won’t work for the patient. This can delay treatment by days. In emergencies, the drug can be given immediately, but the hospital will still require documentation afterward. This system prevents unnecessary spending while allowing flexibility for complex cases.

Mussin Machhour

December 25, 2025 AT 12:36Ben Harris

December 25, 2025 AT 16:55Sophie Stallkind

December 26, 2025 AT 00:37Katherine Blumhardt

December 27, 2025 AT 12:05sagar patel

December 28, 2025 AT 19:54Christopher King

December 30, 2025 AT 05:45Bailey Adkison

December 30, 2025 AT 15:10Gary Hartung

December 30, 2025 AT 20:12Oluwatosin Ayodele

December 31, 2025 AT 10:13Zabihullah Saleh

January 1, 2026 AT 16:04Winni Victor

January 2, 2026 AT 18:06Terry Free

January 3, 2026 AT 14:08Lindsay Hensel

January 3, 2026 AT 21:03Rick Kimberly

January 5, 2026 AT 15:24Jason Jasper

January 7, 2026 AT 02:17