POI Risk Estimator

Assess Your Postoperative Recovery Risk

Enter your surgery details and opioid use to estimate your risk of delayed bowel recovery and recovery time.

Recovery Estimate

After surgery, many patients expect to feel better - but instead, they struggle with bloating, nausea, and an inability to eat or pass gas. This isn’t just discomfort. It’s postoperative ileus (POI), a common and costly complication that delays recovery and extends hospital stays. And in most cases, opioids are the biggest culprit.

POI happens when the gut temporarily stops moving food and gas along. It’s not a blockage. It’s not an infection. It’s a nervous system shutdown triggered by surgery and worsened dramatically by painkillers. Patients might not pass gas for 4 or 5 days. They can’t keep down liquids. Their stomach swells. They’re stuck in bed. And all because the very drugs meant to help them manage pain are slowing their gut to a crawl.

Why Opioids Are the Main Problem

Opioids like morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl are powerful painkillers. But they don’t just work in the brain. They bind to mu-opioid receptors all over the body - including in the walls of your intestines. When they do, they tell the gut to stop contracting. Studies show this can reduce colonic motility by up to 70%. That means food, gas, and stool don’t move. The result? Hard, dry stools, bloating, vomiting, and delayed bowel movements.

Patients on 5-10 mg of morphine per hour post-surgery often see their gastric emptying slowed by 50-200%. That’s not a small delay. That’s a full day or more of being unable to eat. And when patients get more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) in the first 48 hours, they’re over 3 times more likely to have severe bloating and take nearly 3 full days longer to have their first bowel movement compared to those on lower doses.

It’s not just the dose. Even patients who’ve never used opioids before can develop this. The body releases its own natural opioids during surgery, and then doctors add more. The combination is a perfect storm for gut paralysis.

What Happens When the Gut Stops Working

POI isn’t just uncomfortable - it’s expensive and dangerous. On average, it adds 2-3 days to a hospital stay. In the U.S. alone, it costs over $1.6 billion each year. For patients, that means more time in bed, more risk of blood clots, more infections, and more stress.

Standard treatments like nasogastric tubes (NG tubes) rarely help. A Cochrane review found they only reduce POI duration by 12% - barely better than doing nothing. And they’re uncomfortable. Patients hate them.

Meanwhile, symptoms like bloating, reflux, and constipation show up in 40-80% of opioid-treated patients. Some report straining for hours. Others feel like their stomach is full of air. These aren’t minor complaints. They’re signs that the gut is shutting down.

Prevention: The Real Solution

The best way to treat POI? Prevent it before it starts. And the most effective way to do that is to use fewer opioids.

Modern guidelines from the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommend limiting opioid use to under 30 MME in the first 24 hours after surgery. Studies show this cuts POI rates from 30% down to 18%. That’s a massive improvement.

How do you do it? With multimodal analgesia. That means using a mix of non-opioid painkillers together:

- Acetaminophen (IV): 1 gram every 6 hours. It’s safe, effective, and doesn’t slow the gut.

- Ketorolac (IV): 30 mg. A strong NSAID that reduces inflammation and pain without opioids. Avoid if the patient has kidney issues or bleeding risks.

- Regional anesthesia: Spinal or epidural blocks. These numb the surgical area, so patients need far less opioids. In orthopedic surgery, epidurals cut POI duration from 5.2 days to 3.8 days.

Start this combo before surgery - not after. Preemptive pain control works better than trying to catch up later.

Non-Drug Tactics That Actually Work

Medication isn’t the only answer. Simple, low-cost actions make a huge difference.

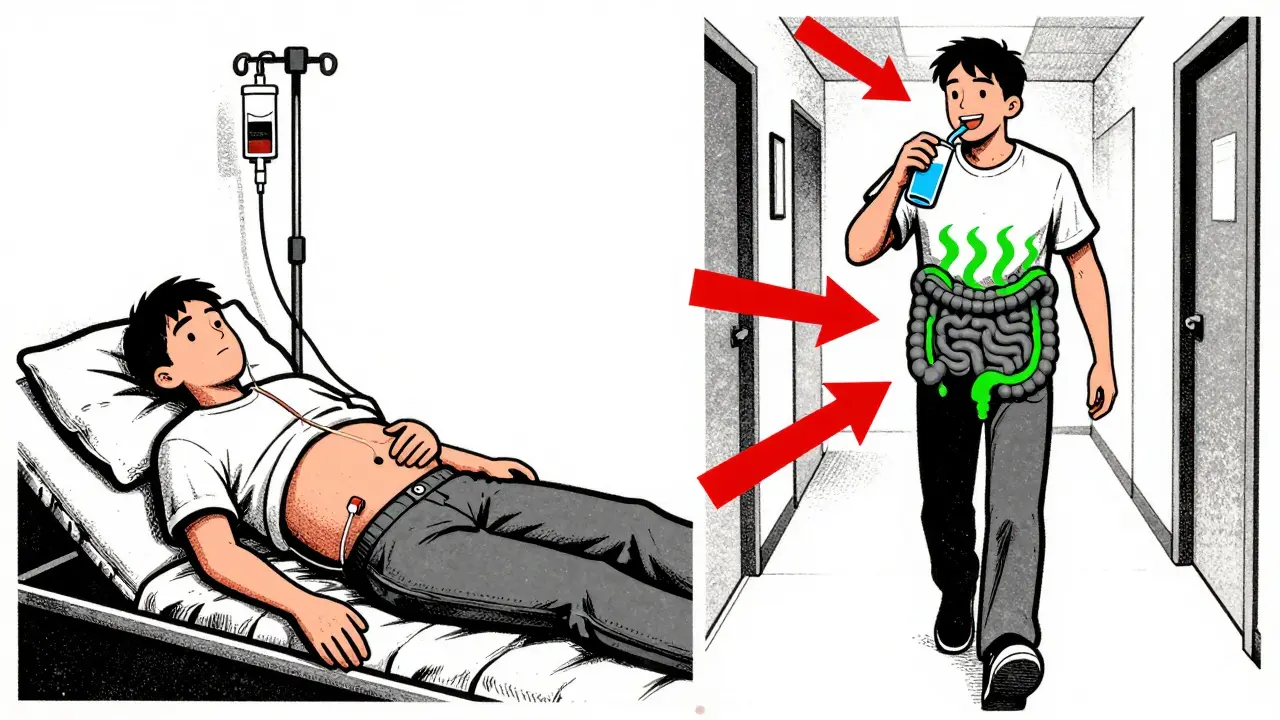

Early movement: Getting patients up and walking within 4 hours of surgery reduces POI duration by 22 hours. Even just sitting in a chair helps. Nurses who push patients to get up early see better outcomes.

Chewing gum: Yes, really. Chewing gum 4 times a day after surgery tricks the brain into thinking food is coming. It triggers gut motility signals. Studies show it cuts POI time by 12-24 hours. It’s free, safe, and patients like it.

Early eating: Don’t wait for bowel sounds. Don’t wait for flatus. If the patient is awake and not vomiting, offer sips of water within 6-12 hours. Then clear liquids. Then soft food. The gut responds to stimulation. Starving it only makes things worse.

One hospital in Michigan tracked 347 patients who followed a simple bundle: gum, early ambulation, and scheduled IV acetaminophen. POI duration dropped from 4.1 days to 2.7 days. No drugs. Just habits.

When Opioids Are Still Needed

Some patients - those with major trauma, severe burns, or complex spine surgeries - still need opioids. But even then, you don’t have to accept POI.

Peripheral opioid receptor antagonists like alvimopan and methylnaltrexone block opioids in the gut without affecting pain relief in the brain. Alvimopan, given orally, reduces time to bowel recovery by 18-24 hours in abdominal surgery. Methylnaltrexone, given as a shot, speeds things up by 30-40% in opioid-tolerant patients.

But they’re not magic. Alvimopan is only approved for short-term use. Methylnaltrexone costs $147.50 per dose. And neither works if there’s a real bowel obstruction (which happens in less than 0.5% of cases).

Use them smartly: If a patient gets over 40 MME in 24 hours, add one. If they’re having major abdominal surgery and are opioid-naive, consider it routine.

Why Many Hospitals Still Get It Wrong

Despite the evidence, many places still rely on old habits. Anesthesia teams are used to giving opioids as the default. Nurses aren’t trained to push early movement. Doctors don’t track opioid doses in MME.

One study found 63% of hospitals faced resistance from anesthesia teams when trying to cut opioids. Only 42% of nurses consistently helped patients walk early. Without buy-in from every team, prevention fails.

Successful programs don’t just change drugs. They change culture. They hold daily "POI rounds" where surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses review every patient: How much opioid did they get? Did they walk today? Did they chew gum? When did they pass gas? They track outcomes. They adjust. They celebrate wins.

At academic centers, 92% use full POI prevention bundles. At rural hospitals? Only 28%. That’s why patients in big cities recover in 3.2 days on average - while those in small towns wait 5.1 days.

The Future: What’s Next

Research is moving fast. A reformulated version of alvimopan is in final trials - it could be back on the market by 2025. AI models are being tested to predict who’s at highest risk for POI using 27 pre-op factors - with 86% accuracy. Fecal transplants are being tried for stubborn cases. Naltrexone implants could deliver long-term gut protection.

But the biggest change won’t come from new drugs. It’ll come from changing how we think about pain.

Pain isn’t the enemy. Unnecessary pain is. And sometimes, the best way to manage pain is to use less of the drugs that cause other problems.

By 2027, experts predict POI prevention will be standard care. The savings? Up to $7.2 billion a year. But that only happens if every hospital - from big cities to small towns - starts treating the gut with the same care as the heart or lungs.

What Patients Should Ask

If you’re scheduled for surgery, ask these questions:

- Will I be on opioids? How much?

- Can we use acetaminophen and ketorolac instead?

- Will I be helped to walk the same day?

- Can I chew gum after surgery?

- Will you let me drink and eat early?

These aren’t radical requests. They’re basic standards of care. And if your care team doesn’t know the answers - it’s time to ask why.

What is postoperative ileus?

Postoperative ileus (POI) is a temporary slowdown or stoppage of the intestines after surgery. It causes bloating, nausea, vomiting, and inability to pass gas or have a bowel movement. It’s not a blockage - it’s a nervous system reaction to surgery and pain medications, especially opioids. It typically lasts more than 3 days and delays recovery.

How do opioids cause postoperative ileus?

Opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors in the gut wall, which slows or stops the muscle contractions that move food and gas. This reduces colonic motility by up to 70%. The effect is dose-dependent: higher opioid doses lead to longer delays in bowel function. Even small amounts can cause hard stools, bloating, and delayed flatus within 24-72 hours after surgery.

Can I avoid opioids after surgery?

Yes, and it’s often safer. Multimodal analgesia - combining acetaminophen, NSAIDs like ketorolac, and regional anesthesia (epidural or spinal) - can control pain just as well as opioids, without slowing the gut. Studies show this reduces POI incidence by 25-35%. You may still need opioids for severe pain, but starting with non-opioid options first is the standard of care.

What are the best non-drug ways to prevent postoperative ileus?

Three proven, low-cost methods: (1) Get up and walk within 4 hours after surgery - even just sitting in a chair helps. (2) Chew sugar-free gum 4 times a day - it tricks your gut into starting motility. (3) Drink clear liquids and eat soft food as soon as you’re awake and not nauseous. These simple steps can cut recovery time by a full day.

Are drugs like methylnaltrexone or alvimopan worth using?

For high-risk patients - like those having abdominal surgery or receiving high opioid doses - yes. Methylnaltrexone (shot) and alvimopan (pill) block opioid effects in the gut without reducing pain relief. They cut recovery time by 18-40%. But they’re expensive ($147+ per dose) and not needed for low-risk patients. Use them when opioid doses exceed 40 MME in 24 hours or if you’re having major abdominal surgery.

How long does postoperative ileus last?

Without intervention, POI typically lasts 3-5 days. With good prevention - early movement, gum chewing, and low opioids - it can be cut to 2-3 days. In high-risk patients on high opioids, it may last over 5 days. The goal is to get bowel function back within 72 hours of surgery.

Is postoperative ileus dangerous?

It’s not usually life-threatening, but it’s serious. It increases risk of blood clots, pneumonia, and infections because patients stay in bed longer. It delays discharge, adds $2,300+ to hospital costs per patient, and can lead to readmissions. In rare cases, if untreated, it can progress to a true bowel obstruction.

Can chewing gum really help my gut recover?

Yes. Chewing gum activates the cephalic phase of digestion - the same reflex triggered when you see or smell food. It signals the brain to start gut motility. Studies show patients who chew gum 4 times a day after surgery pass gas and have bowel movements 12-24 hours sooner than those who don’t. It’s free, safe, and easy.

Why do some hospitals still use high doses of opioids?

Many teams are used to treating pain with opioids as the first option. There’s often no system to track opioid doses in morphine milligram equivalents (MME), and staff aren’t trained on alternatives. Changing this takes time, education, and leadership. Hospitals with dedicated ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) programs have the best outcomes.

What’s the bottom line for patients and families?

Ask for less opioid painkillers. Ask to get up and walk the same day. Ask to chew gum. Ask to drink and eat early. These aren’t requests - they’re proven, evidence-based steps that reduce complications and get you home faster. If your care team doesn’t know about them, share this information. You have the right to the best recovery possible.

Simon Critchley

February 9, 2026 AT 00:52Jesus Christ, this is peak ERAS protocol gold. Opioids are the silent killers of gut motility-70% reduction in colonic contractions? That’s not a side effect, that’s a full-on GI mutiny. We’re talking about a pharmacological chokehold on the enteric nervous system. And yet hospitals still default to morphine like it’s 1998. The gum thing? Genius. It’s cephalic-phase stimulation on a stick. No drugs, no tubes, just mastication tricking the vagus into thinking dinner’s coming. I’ve seen it cut POI by 24 hours in post-op colectomy patients. Why isn’t this in every OR protocol? Because change is hard. And bureaucracy hates evidence.

Tom Forwood

February 10, 2026 AT 11:20John McDonald

February 11, 2026 AT 19:03Let’s be real-the real villain here isn’t opioids, it’s inertia. Anesthesia teams are trained to treat pain with opioids because that’s what they’ve always done. Nurses aren’t incentivized to get patients up. Admins don’t track MME. We’re not failing patients because we’re cruel-we’re failing them because we’re lazy. The solution isn’t more drugs. It’s better systems. Daily POI huddles. Checklists. Rewarding units that hit 90% compliance. We do this for sepsis and catheter infections. Why not POI? It’s cheaper, safer, and more humane. Let’s stop treating prevention like an afterthought.

Joshua Smith

February 12, 2026 AT 05:27Monica Warnick

February 13, 2026 AT 00:12Okay but what if you’re one of those people who gets addicted to opioids after ONE dose? Like… what if the system is designed to make you dependent? I mean, think about it. Hospitals push opioids because they’re easy. They’re fast. They’re profitable. The pharma companies fund the guidelines. The nurses are overworked. The doctors are burnt out. And the patient? They’re just a number on a bed. This isn’t medicine. It’s a slow, silent epidemic. And they call it ‘standard care’ while you’re bloated and crying because you can’t even burp. Someone’s making money off your discomfort. Always is.

Ashlyn Ellison

February 14, 2026 AT 09:39Ryan Vargas

February 16, 2026 AT 07:23Let’s not pretend this is about medical science. This is about control. The opioid crisis didn’t start in Appalachia-it started in the OR. Hospitals didn’t just overprescribe-they normalized dependency as ‘standard.’ They turned gut paralysis into a revenue stream: longer stays, more IVs, more monitoring, more readmissions. The fact that alvimopan costs $147 per dose? That’s not a drug. That’s a ransom. And the real conspiracy? The FDA approved it… then pulled it… then let it back in… all while hospitals kept using opioids like candy. Who benefits? The ones who profit from prolonged hospitalization. Not the patient. Never the patient.

Sam Dickison

February 17, 2026 AT 18:42Preemptive multimodal analgesia is the MVP. IV acetaminophen + ketorolac + regional block? That’s the holy trinity. You don’t need opioids unless the patient’s screaming and you’ve tried everything else. I work in trauma. We do this daily. Patients are happier. Nurses are happier. Costs drop. Recovery time? Cut in half. The only resistance comes from old-school docs who think ‘if it ain’t morphine, it ain’t pain control.’ Sorry, but your 1990s pain protocol is outdated. We’re not in the Wild West anymore. The gut’s got rights.

Karianne Jackson

February 17, 2026 AT 19:25Chelsea Cook

February 17, 2026 AT 23:25Let me get this straight-you’re telling me the solution to a medical complication is… chewing gum? And walking? And not giving opioids? Oh my god. That’s like saying the cure for a broken leg is… not hitting it with a hammer. I’m not shocked this works. I’m shocked it’s not mandatory. If your hospital doesn’t have a gum policy, fire the administrator. Put a sign on the wall: ‘If you don’t offer gum, you’re not a hospital. You’re a waiting room with a bed.’

Andy Cortez

February 18, 2026 AT 07:08Jacob den Hollander

February 19, 2026 AT 18:14Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. My mom had colorectal surgery last year. They used the full bundle-gum, early ambulation, IV acetaminophen, no opioids beyond 24 hours. She was home in 48 hours. No NG tube. No IVs. Just her, a walker, and a bag of sour patch kids. She said chewing gum was the only thing that made her feel like she was still alive. I’ve never seen her so proud of her recovery. This isn’t just data. This is dignity. If your hospital doesn’t do this, ask why. And if they can’t answer? Ask for a transfer. You deserve better.

glenn mendoza

February 20, 2026 AT 06:06It is with profound respect for the evidence-based principles outlined herein that I offer the following observation: The integration of non-pharmacological interventions such as early ambulation and masticatory stimulation constitutes not merely an adjunct, but a paradigmatic shift in perioperative care. The data are unequivocal. The cost-benefit ratio is unparalleled. The ethical imperative is undeniable. I respectfully urge all healthcare institutions to adopt the ERAS protocol in its entirety, not as an option, but as the new standard of care. The future of surgical recovery is not pharmacological-it is physiological, patient-centered, and profoundly humane.